Reduced Oxygen in Ice Age Antarctic Ocean Gives Clue to 'Missing' Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide

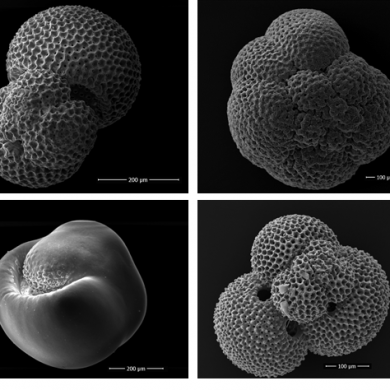

The scientists were able to infer past ocean conditions, using foraminifera preserved in sediment cores

Researchers infered past ocean conditions using foraminifera preserved in sediment cores taken from an underwater mountain in the Amundsen Sea.Images courtesy of University of OxfordDr Babette Hoogakker and Professor Ros Rickaby of the University of Oxford Department of Earth Sciences are co-authors on a paper which offers a better understanding of where and how atmospheric carbon dioxide was sequestered from the atmosphere during ice ages. The paper also included data from a 4th-year undergraduate project undertaken in the department by Luke Jones.

Researchers infered past ocean conditions using foraminifera preserved in sediment cores taken from an underwater mountain in the Amundsen Sea.Images courtesy of University of OxfordDr Babette Hoogakker and Professor Ros Rickaby of the University of Oxford Department of Earth Sciences are co-authors on a paper which offers a better understanding of where and how atmospheric carbon dioxide was sequestered from the atmosphere during ice ages. The paper also included data from a 4th-year undergraduate project undertaken in the department by Luke Jones.

Led by Assistant Professor Zunli Lu of the Syracuse University Department of Earth Sciences, the team of international collaborators explored the question of carbon dioxide storage in the oceans. The scientists were able to infer past ocean conditions, using foraminifera preserved in sediment cores taken from an underwater mountain in the Amundsen Sea, which is part of the ocean surrounding Antarctica. Their study on the ocean records, trapped in foraminifera shells, is published in Nature Communications.

Although it is accepted that atmospheric carbon dioxide was sucked deep into the ocean during ice ages, quantitative measures of how much was stored, and in what chemical form, have been hard to come by. One way to track carbon dioxide storage is by investigating its partner in respiration: oxygen. Plankton photosynthesize near the ocean surface, taking in carbon dioxide. When the plankton die and sink to the ocean floor, the reverse process, respiration, happens. Respiration uses up oceanic oxygen and re-releases carbon dioxide in the deep ocean. Because of this relationship, low oxygen levels in a specific part of the ocean can flag where atmospheric carbon dioxide was stored during glacial periods.

While past oceanic oxygen levels can provide insight to global carbon dioxide cycling, reconstructing past oxygenation conditions is quite a challenge. Enter foraminifera. Foraminifera have an external shell made of calcium carbonate, which traps signatures of their environment as they grow—including oxygen levels. These climate-related signatures are often preserved for millions of years in sediments accumulated on the ocean floor.

Lu has spent years measuring iodine in calcium carbonate as a proxy for tracking oceanic oxygen levels. “These carbonates recorded almost the entire Earth’s history , and we have one of the best ways of translating the oxygen stories out of these rocks and fossils” he says. Unlike most other oxygen proxies, iodine is able to detect relatively subtle changes in oxygen levels, not just presence or absence of the gas in seawaters.

Babette Hoogakker seconds the power of this new proxy: “Its application allows the assessment of open ocean subsurface oxygenation states using planktonic foraminifera, which until now was virtually impossible.”

Foraminifera from the group’s study site in the high-latitude Antarctic indicate that the surrounding Southern Ocean reached very low levels of oceanic oxygen during ice ages. Co-author Ros Rickaby says, “It was a real surprise to discover that any part of the Southern Ocean, which today is so rich in oxygen, evolved naturally to contain such small amounts of this influential gas during the glacial period.”

Co-author Claus-Dieter Hillenbrand of the British Antarctic Survey says, “Physical, chemical and biological changes in the World Ocean in general, and in the Southern Ocean in particular, played a crucial role for glacial-interglacial variations in atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and global climate change.”

Related Article: The Previously Unknown Microbial "Drama" of the Southern Ocean

Or as Lu puts it: “The Southern Ocean is like a tap for CO2. When you open the tap, CO2 goes into the atmosphere and it becomes warm globally. When you partially shut that valve during an ice age, CO2 becomes lower in the atmosphere.” Lu says that finding low oxygen in the high-latitude Southern Ocean gives insight into how the “valve” works during ice ages, and moreover points to the oxygenation conditions in vast volumes of deep waters connected to the Southern Ocean through ocean circulation.

Lu and colleagues hope that understanding the past cycles will give researchers foresight into the effects of modern and future global changes. While the level of atmospheric carbon dioxide routinely cycled between 200 and 280 parts per million in the past, the planet is currently faced with levels of 400 parts per million of the gas. “If we can explain the naturally oscillating recent climate, we may be able to make predictions for how modern warming might cause the marine environment to change in the future,” Lu says.