Amid Environmental Change, Lakes Surprisingly Static

Researchers found that, “despite large environmental change and management efforts over recent decades, water quality of lakes in the Midwest and Northeast U.S. has not overwhelmingly degraded or improved”

A new study by UW–Madison graduate student Samantha Oliver (above) says despite major environmental changes and water quality management efforts, most Midwestern and Northeastern lakes have not overwhelmingly degraded or improved over recent decades.IMAGE COURTESY OF SAMANTHA OLIVER

A new study by UW–Madison graduate student Samantha Oliver (above) says despite major environmental changes and water quality management efforts, most Midwestern and Northeastern lakes have not overwhelmingly degraded or improved over recent decades.IMAGE COURTESY OF SAMANTHA OLIVER

In recent decades, change has defined our environment in the United States. Agriculture intensified. Urban areas sprawled. The climate warmed. Intense rainstorms became more common. But, says a new University of Wisconsin–Madison study, while those kinds of changes usually result in poor water quality, lakes have surprisingly stayed the same.

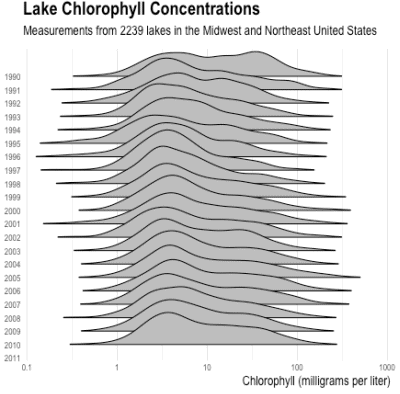

The authors of the article, published online Wednesday in the journal Global Change Biology, assessed changes in measures of water quality, including plant nutrients and algal growth, in 2,913 U.S. lakes from 1990 to about 2011. The researchers found that, “despite large environmental change and management efforts over recent decades, water quality of lakes in the Midwest and Northeast U.S. has not overwhelmingly degraded or improved.”

Samantha OliverIMAGE COURTESY OF SAMANTHA OLIVERThat doesn’t mean there were no notable trends. For example, 10 percent of the study lakes were getting “greener,” or seeing more algae blooms and plant growth, while only five percent were experiencing clearer water conditions. Still, the vast majority of lakes were stuck in a sort of water quality status quo.

Samantha OliverIMAGE COURTESY OF SAMANTHA OLIVERThat doesn’t mean there were no notable trends. For example, 10 percent of the study lakes were getting “greener,” or seeing more algae blooms and plant growth, while only five percent were experiencing clearer water conditions. Still, the vast majority of lakes were stuck in a sort of water quality status quo.

The meaning of these results depends on your perspective, says Samantha Oliver, lead author of the report and a graduate student at UW–Madison’s Center for Limnology.

On the one hand, the U.S. spends $3.5 billion each year on efforts to keep nutrients and the algae they feed out of our waterways. So the fact that there are no large-scale positive trends in water quality is dispiriting. But, considering that intensifying agriculture, warming climate, and more intense rain events are known to boost nutrient runoff and algae blooms, the lack of a nationwide negative trend in water quality may be a heartening sign that management practices are at least holding the line.

Related Article: Shaking the Nanomaterials Out: New Method to Purify Water

Scientists’ reaction to these results, says Oliver, is “a glass half full, glass half empty thing. Some people say, ‘Whoa, the management must really be doing something,’ and the other half of them say, ‘That’s really depressing, our management hasn’t done anything. We need to do so much more!’”

Oliver’s study assessed changes in measures of water quality, including plant nutrients and algal growth, in 2,913 U.S. lakes from 1990 to about 2011.Image credit: Nicole Smith, Michigan State University

Oliver’s study assessed changes in measures of water quality, including plant nutrients and algal growth, in 2,913 U.S. lakes from 1990 to about 2011.Image credit: Nicole Smith, Michigan State University

Her take is that government policies, such as the Clean Water Act’s limits on urban and agricultural runoff or the Clean Air Act’s limits on nitrogen and carbon pollution, do make a difference. “If our water quality improvement efforts hadn’t been in place, conditions could have been a lot worse,” she says. “It’s fair to say that these protections do matter.”

But, Oliver says, the study’s bigger take-home message is one of scale.

Management efforts are often focused on improving conditions of a single lake. While those efforts may pay off locally and result in better water quality in that lake, these little victories don’t always add up to a bigger win. For example, one part of a stream may get cleaner when best-management farming practices are used in a nearby field, but those improvements can get washed away by poor management of the next field downstream.

You can see this example play out, Oliver says, in the annual “dead zone” that develops in the Gulf of Mexico. As fertilizer used on Midwestern corn and soybeans runs off fields and into nearby streams, it ends up, eventually, in the Mississippi River. The Mississippi releases those nutrients into the gulf, where they feed huge algae blooms that develop, die, and decompose—a process that consumes the available oxygen in the water, killing fish and making conditions uninhabitable for other marine life.

You can see this example play out, Oliver says, in the annual “dead zone” that develops in the Gulf of Mexico. As fertilizer used on Midwestern corn and soybeans runs off fields and into nearby streams, it ends up, eventually, in the Mississippi River. The Mississippi releases those nutrients into the gulf, where they feed huge algae blooms that develop, die, and decompose—a process that consumes the available oxygen in the water, killing fish and making conditions uninhabitable for other marine life.

Dealing with the “dead zone” or any other large-scale problem won’t be a matter of simply improving conditions at the local level, Oliver says.

“The environmental changes that are happening in the world today are happening everywhere, they aren’t happening in a single lake or a single stream,” she says. “While we like to focus on ‘our’ particular lake or stream, each one is different. How the whole population of lakes and streams, and ultimately, the Gulf of Mexico will respond to things like climate change or government policies can only be figured out by looking at the bigger picture of the thousands of lakes and rivers across the U.S.”