Synthetic Plant Hormones Shut Down DNA Repair in Cancer Cells

The Georgetown researchers are the first to investigate the hormone for its anti-cancer properties

WASHINGTON — Two drugs that mimic a common plant hormone effectively cause DNA damage and turn off a major DNA repair mechanism, suggesting their potential use as an anti-cancer therapy, say investigators at Georgetown University Medical Center. Their study is published online in Oncotarget.

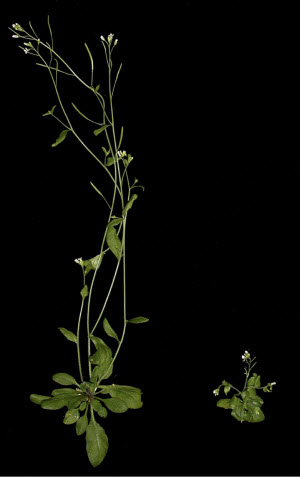

Researchers found that synthetic plant hormones halt the DNA repair process that occurs after the cell’s DNA is copied and before it divides.Photo credit: William M. Gray, Wikimedia CommonsThe agents, MEB55 and ST362, are a synthetic version of strigolactones, a class of plant hormones made in roots that regulate development of plant roots under ground and shoots above ground.

Researchers found that synthetic plant hormones halt the DNA repair process that occurs after the cell’s DNA is copied and before it divides.Photo credit: William M. Gray, Wikimedia CommonsThe agents, MEB55 and ST362, are a synthetic version of strigolactones, a class of plant hormones made in roots that regulate development of plant roots under ground and shoots above ground.

The Georgetown researchers are the first to investigate the hormone for its anti-cancer properties and since 2009 have led a series of studies showing that synthetic versions of strigolactones can shut down cancer growth in breast, prostate, colon, lung, and a variety of other tumor cells. Their new study reveals the mechanisms of the plant hormone and how it can be lethal in human prostate cancer cells when combined with another cancer drug.

“MEB55 and ST362 appear to be very promising agents. Our study suggests that when used with anti-cancer drugs called PARP inhibitors, the combination is effective and does not harm normal cells,” says the study’s senior investigator, Ronit Yarden, PhD, assistant professor in the department of human science at the Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies and a member of Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Her collaborators include researchers at ARO, Israel and University of Turin, Italy who first synthesized MEB55 and ST362. Using a technique developed at Georgetown called conditionally reprogrammed cells, which allows cells to grow indefinitely, investigators were able to study the agents in a patient’s prostate cancer cells.

Related Article: Orange Lichens Are Source for Potential Anticancer Drug

The study shows that when either MEB55 or ST362 are combined with a PARP inhibitor, the cells die. The synthetic plant hormones halt the DNA repair process that occurs after the cell’s DNA is copied and before it divides. The PARP inhibitor shuts down a second repair pathway, leaving cancer cells with no alternative but to die. “Mistakes in copying DNA are especially prevalent in cancer cells, so without any way to repair their DNA, these cells self destruct,” Yarden says.

The idea to use PARP inhibitors comes from its use in breast and ovarian cancer, where cancers develop due to mutated BRCA1/BRCA2 genes, she says. The BRCA genes, when normal, control a DNA repair pathway, but when mutated, cannot repair genes—the same effect offered by the synthetic hormones.

Yarden says she expects to soon test the combination of agents in animal models of varied cancers.

Researchers participating in the study are, from Georgetown, Michael Croglio, Jeff M. Haake, Colin P. Ryan, Victor S. Wang, Jennifer Lapier, Jamie P. Schlarbaum, Yaron Dayani, PhD, Jeannine R. LaRocque, PhD, and Christopher Albanese, PhD; Emma Artuso and Cristina Prandi, PhD, from the University of Turin; Hinanit Koltai, PhD, from ARO (Agricultural Research Institute), Israel; Keli Agama, PhD, and Yves Pommier, MD, PhD, from the National Cancer Institute; and Yu Chen, MD, PhD, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Georgetown University and ARO have filed patent applications in the US, Israel and other countries for the technology described in this paper. Yarden and co-authors Prandi and Koltai are named as inventors.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA051008) and Georgetown University including a Georgetown University Undergraduate Research Opportunity Fellowship and Georgetown University Raines Fellowship. Additional funding was provided by the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1TR001409-01) and the Department of Defense (PC140268 and W81XWH-13-1-0327).