Cutting-Edge Fingerprint Technology Could Help in the Fight Against Knife Crime

Over the decades a multitude of techniques have been developed for enhancing the visualisation of hidden fingermarks

University of Nottingham

University of Nottingham

Dr James Sharp, from the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Nottingham led the research. He said: “This raises the possibility of being able to reliably visualise fingerprints on surfaces previously thought to be devoid of such crucial evidence. ToF-SIMS imaging has the potential and could be a valuable tool in helping to visualise fingermarks on objects such as stainless-steel knife blades and firearms.”

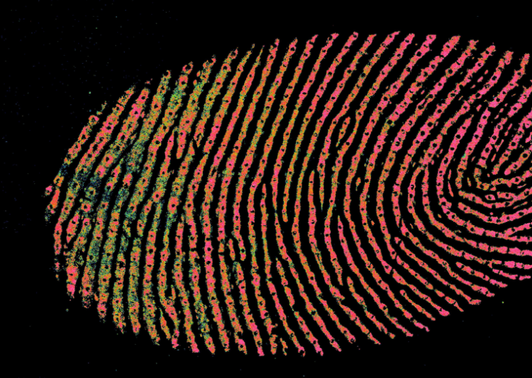

The fingerprint

In 1902 London burglar, Harry Jackson, became the first man in England to be convicted for a crime based on fingerprint evidence. Since then fingerprints have been regarded as indisputable evidence. But the case of Shirley McKei in 1999 showed that fingerprint evidence can be flawed.

Over the decades a multitude of techniques have been developed for enhancing the visualisation of hidden fingermarks. But substrates such as simple metals and alloys have stubbornly refused to give up their fingerprint secrets – until now.

Adam Long, Undergraduate Programme Coordinator for Forensic Science at the University of Derby, said: “Fingerprints are incredibly difficult to retrieve from metallic surfaces. This is mainly due to physical and environmental conditions that the prints may be exposed to at the crime scene, the age of the print, as well as how the developing agents react with the surface.

“A common example of the difficulties investigators face, comes from examining fired bullet casings. The high temperatures, pressure and friction caused when a bullet is fired makes fingerprints extremely fragile and this, combined with other factors, often results in their apparent removal or obliteration. This technique is non-destructive and can be used repeatedly to image fingerprint marks without compromising their quality.”

The Study

The research team took fingermarks from six donors, every day for 14 days. The fingerprints were put on to disks of brass, aluminium and stainless steel and treated simultaneously so the effects of ageing could easily be determined.

The results showed that the fingerprints developed using traditional techniques were unreliable. Quality degraded after 8 days. Some prints were unrecognisable within 3 days, and one sample showed no results at all after the 14 days.

Being able to measure a mass of different molecules in an individual sample, the Ion beam from the ToF-SIMS technique was able to detect and visualise the fingerprint secretions in samples up to 26 days after they were taken – the first time this has ever been done.

The results were the same for all donors – irrespectively of gender, age and ethnicity.

The fingermarks used in this study were produced to contain consistent levels of eccrine and sebaceous secretions. However, real-world samples are likely to contain variable amounts of these deposits and further studies are required to demonstrate the applicability of ToF-SIMS to a broader range of fingermarks and samples surfaces.

Combination of expertise

Dr Ian Turner, Associate Professor at the University of Derby said “This research project has shown the impact of combining the expertise of leading physicists and forensic scientists has had on developing fingermarks on this challenging surface.”

This technique is of interest to the East Midlands Special Operations Unit – Forensic Services who helped develop the conventional marks used in the study.

Vickie Burgin, Deputy Head of Forensic Services, East Midlands Special Operations Unit said: “We developed the conventional marks using a process called Superglue Fuming at our forensic labs.

“The process works by placing non-porous or semi-porous items into a specialist chamber. A small amount of superglue inside the chamber is then heated and vaporises. This then attracts any salt or chlorides present within sweat in order to reveal fingerprints.

“EMSOU are excited about the opportunities that this new technique offers in developing fingermarks on challenging surfaces.

“This innovative approach could help us to identify suspects and revisit historical crimes where success has - in the past - been low. I look forward to seeing where this collaborative working can take us in the future.”