Dicty forming fruiting bodies, a cooperative act that helps to disperse their spores but also provides an opportunity for cheating.Image credit: STRASSMANNAnyone who has crawled along in the left lane while other drivers raced up the right lane, which was clearly marked “lane ends, merge left,” has experienced social cheating, a maddening and fascinating behavior common to many species.

Dicty forming fruiting bodies, a cooperative act that helps to disperse their spores but also provides an opportunity for cheating.Image credit: STRASSMANNAnyone who has crawled along in the left lane while other drivers raced up the right lane, which was clearly marked “lane ends, merge left,” has experienced social cheating, a maddening and fascinating behavior common to many species.

Although it won’t help with road rage, scientists are beginning to understand cheating in simpler “model systems,” such as the social amoeba, Dictyostelium discoideum.

At one stage in their life cycle thousands of the normally solitary Dicty converge to form a multicellular slug and then a fruiting body, consisting of a stalk holding aloft a ball of spores. It is during this cooperative act that the opportunity for cheating arises.

Some amoebae ultimately become cells in the stalk of the fruiting body and die, while others rise to the top, and form spores that pass their genes to the next generation. When unrelated amoebae gather to form a fruiting body, some strains may overcontribute to the spores and undercontribute to the stalk. These are the cheaters.

Scientists knew that cheaters could be found in wild populations of Dicty, but whether this was a successful strategy in the game of natural selection was anyone’s guess.

Now the ease and low cost of genome sequencing has finally made it possible to answer the question. “By looking at the genetic variation in or near Dicty’s ‘social genes,’ scientists are able to tell whether variants of these genes that made cooperators into cheaters had swept through populations, fought to maintain a toehold, or been given a pass because they didn’t affect survival,” said Elizabeth Ostrowski, PhD, assistant professor of biology and biochemistry at the University of Houston.

“The genome signatures we found suggest neither the cheating nor the cooperating variants of the social genes was able to take over the populations and that the variants had battled to a standstill,” said David C. Queller, PhD, the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Biology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“A stalemate is maintained only in a complex environment where it’s unclear which strategy will win,” said Joan Strassmann, PhD, the Charles Rebstock Professor of Biology in Arts & Sciences. “If the rules never change, the gene that is best on average will eventually drive out the other variant.”

The findings suggest the benefits of cheating change with its frequency, or prevalence, in a population. Cheaters may succeed, for example, only when they are rare, and fail when they become so numerous they push out cooperators or put pressure on cooperators to find ways to defeat cheating.

Many social behaviors are like this, Queller said; the success of one individual’s strategy depends on how many others are also employing it.

The study, described in the June 4 issue of Current Biology, is the work of a collaboration of scientists from Washington University, the University of Houston and the Baylor College of Medicine. Ostrowski is the first author on the paper and Queller and Strassman are senior authors.

An arms race or trench warfare?

“For this project, we sequenced 20 Dicty strains we had isolated from the soil in the eastern U.S. We then looked for variation in 140 genes implicated in social behavior, comparing them to the rest of the genome to see if the social genes were evolving differently,” Strassmann said.

“We originally got enough funding to sequence two genomes,” she said. “But by the time we had cleaned the clones up, the price of sequencing had dropped so much we were able to sequence many more.”

The 140 genes, Queller said, were ones that had been located during an earlier genome-wide screen for genes, that when they are disabled, turn a cooperating amoeba into a cheater.

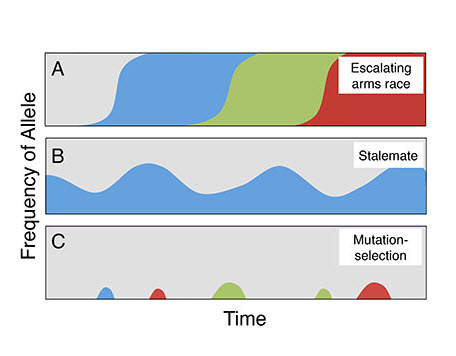

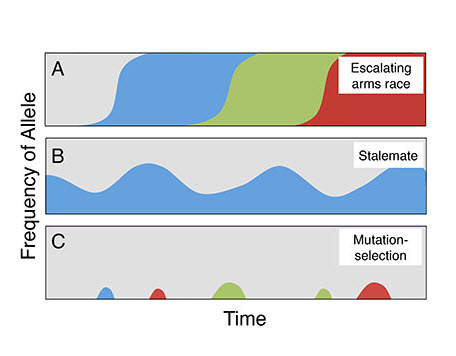

Scenarios for the evolutionary dynamics of cheating behaviors. In the arms race (top), epidemics of cheating and resistance successively sweep through populations. In the stalemate (middle), cheating becomes endemic but does not take over the population. In the mutation and selection scenario (bottom), cheating mutations keep popping up but are quickly removed by selection. Different colors represent different alleles, or variants, of the social genes.Image credit: Social genesThe scientists framed their study by defining several hypothetical scenarios for the evolutionary dynamics of cheating behaviors in Dicty (illustrated above), each of which makes different, testable predictions about DNA diversity in and near the social genes.

Scenarios for the evolutionary dynamics of cheating behaviors. In the arms race (top), epidemics of cheating and resistance successively sweep through populations. In the stalemate (middle), cheating becomes endemic but does not take over the population. In the mutation and selection scenario (bottom), cheating mutations keep popping up but are quickly removed by selection. Different colors represent different alleles, or variants, of the social genes.Image credit: Social genesThe scientists framed their study by defining several hypothetical scenarios for the evolutionary dynamics of cheating behaviors in Dicty (illustrated above), each of which makes different, testable predictions about DNA diversity in and near the social genes.

“We thought we were going to see the signature of an arms race in the DNA,” Queller said, “because the cheater/cooperator conflict seems analogous with other kinds of conflict, such as host/pathogen conflict, that produce escalating battles between adaptations.”

An arms race, technically a series of “selective sweeps,” would have shown up as a lack of variation in the DNA in or near the social genes, because a highly advantageous gene “sweeps” through a population. “What we found was kind of the opposite,” Queller said. “Instead of diminished variation, there was more variation in the social genes than average, which is consistent with a prolonged stalemate at these locations.”

The scientists found more evidence for a stalemate when they compared strains from two different populations, one in Texas and the other in Virginia, Queller said.

In an arms race, the Dicty at these geographically separated locations would probably have undergone different selective sweeps, which in turn would make the two populations less similar. In fact, however, the populations differed less at the social gene locations than at other genes, suggesting that some selective force was working to maintain the same variants of the social genes in both the Texas and Virginia populations.

Both the increased genetic diversity near the social genes and the failure of separated populations to drift apart at those genetic locations support the stalemate scenario.

“We failed to observe the genetic signatures of a simple arms race: a reduction in genetic diversity and long-term divergence of populations,”Ostrowski said. “Rather, the genetic signatures suggests there is trench warfare among variants of the social genes, and neither the cheaters or the cooperators are able to gain the upper hand.”

But why is that? Ostrowski said. “What limits the spread of cheaters? Are they suppressed by better cheaters or by a resistant population? And conversely what limits cooperators? Why don’t the cooperators completely shut down the cheaters?”

It’s hard to imagine questions of more universal interest.