Measuring Chemicals in Cannabis

As the industry grows, so does the increased need for potency testing.

Medicinal cannabis is legal in more than half of the United States, plus a collection of countries around the world, including Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, Mexico, and Poland, with more probably likely to follow suit. Consequently, cannabis-based products made for medical purposes need to be tested for potency to ensure the proper dose. What’s more, cannabis used for recreational purposes should also be tested. Despite the youth of this industry, applicable analytical techniques do exist.

Cannabis contains dozens of cannabinoids, which are usually cited for their medicinal qualities. In addition, cannabis contains various tetrahydrocannabinols (THCs), which provide the plant’s euphoric effects. The question is: Which ones should be measured for a product’s potency? The answer depends on who is doing the testing. Different organizations or states can set up their own testing requirements. In many cases, those regulations remain in development. Commonly, labs will test for tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A (THCA) and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and report “total potency,” because THCA rapidly converts to THC under drying, manufacturing, and pyrolytic conditions. (Editor’s note: See the comparisons between CBD and THC here.)

In this analysis of a 10-compound cannabinoid mix with the Agilent 1290 Infinity II UHPLC-6230B LC-TOF-MS system, chromatogram A is the UV signal at 280 nanometers, and B–G are the LC-TOF-MS-extracted ion chromatograms for each cannabinoid.Image courtesy of AgilentAs this industry develops, even more components could be tested. As examples, Bob Clifford, general manager of marketing at Shimadzu Scientific Instruments (Columbia, MD), says there is “growing interest in tetrahydrocannabivarin acid (THCVA), cannabidivarinic acid (CBDVA), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA), but standard reference materials may be difficult to purchase.”

In this analysis of a 10-compound cannabinoid mix with the Agilent 1290 Infinity II UHPLC-6230B LC-TOF-MS system, chromatogram A is the UV signal at 280 nanometers, and B–G are the LC-TOF-MS-extracted ion chromatograms for each cannabinoid.Image courtesy of AgilentAs this industry develops, even more components could be tested. As examples, Bob Clifford, general manager of marketing at Shimadzu Scientific Instruments (Columbia, MD), says there is “growing interest in tetrahydrocannabivarin acid (THCVA), cannabidivarinic acid (CBDVA), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA), but standard reference materials may be difficult to purchase.”

The increasing list of components to test creates part of the challenge. In addition, other chemicals in cannabis make it more difficult to measure the ones of interest. The cannabis also gets processed in various ways, which means that both the raw material and the final product need to be tested in some cases, particularly where the product is intended as a therapy. Getting all that right requires the appropriate equipment, methods, and operators.

METHODS FOR MEASURING

Anthony Macherone, senior scientist at Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA) and visiting professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD), says that the company has “multiple platforms [for cannabis potency testing], ranging from high-performance liquid chromatography, HPLC, with an ultraviolet, UV, detector to LC plus time-of-flight mass spectrometry, LC-TOF-MS.”

Other vendors also use similar approaches. Clifford calls HPLC with a UV detector the “gold standard” for measuring the most commonly tested components of cannabis. He adds, “The important goals for cannabis testing are ruggedness and repeatability along with quantitative accuracy.”

For the main components of cannabis, HPLC/UV provides a fast and economical test. For even faster runs, a lab can use ultra-HPLC (UHPLC). This technology, though, is more expensive.

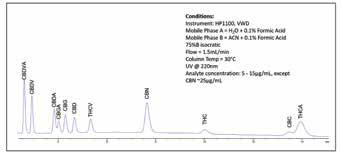

HPLC can reveal a range of chemicals in cannabis.Image courtesy of Emerald ScientificTo get a more in-depth measurement of a cannabis sample, more advanced technology is required. “It has been reported there are more than 130 lesser-known cannabinoids,” Clifford says. These can be identified with various forms of mass spectroscopy.

HPLC can reveal a range of chemicals in cannabis.Image courtesy of Emerald ScientificTo get a more in-depth measurement of a cannabis sample, more advanced technology is required. “It has been reported there are more than 130 lesser-known cannabinoids,” Clifford says. These can be identified with various forms of mass spectroscopy.

Someone could buy the equipment and set up a cannabis-testing lab, but what is required to run one? According to Macherone, it requires someone at the “technician level for basic HPLC-UV quantitation of cannabinoids." For cannabinoid research and drug discovery/development, he says, someone with a PhD should be in charge.

Some cannabis lab personnel lack the desired chemistry background for these advanced analytical platforms. “To help overcome the differences in education/experience, Shimadzu introduced a platform for the nonscientist called the Cannabis Analyzer for Potency that allows nonchromatographers to use the system,” Clifford says.

Other vendors also work on technologies that make it easier for labs to complete the necessary testing. Agilent, says Macherone, “offers a platform-agnostic solution that best fits the lab’s current and future needs.”

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

Someone setting up a new cannabis-testing lab can also turn to Emerald Scientific (San Luis Obispo, CA). Chief technology officer Amanda Rigdon describes the company as a “supplier of lab reagents and equipment dedicated to the cannabis analytical industry.”

This company consults with customers about what they need, as well as what they can afford. “The finances vary widely, from someone who sold a car to buy an instrument on eBay to someone with $1.5 million in investment money,” Rigdon says. The desired throughput also matters. A customer needs to buy a system that will meet his or her requirements, and—if needed—expand to new capabilities in the future.

Beyond the instrumentation, Emerald Scientific also provides customers with protocols to test for potency. Rigdon runs her own lab at the company, where she can test new methods, and she is working on validating them. Whatever protocol a lab runs, she says, “being successful is in the details.” If a customer runs into trouble, Rigdon does what she can to solve the problem. She’ll even review data if a customer allows that. She says that some of her customers have taught themselves HPLC. “It can be done,” she points out, “but having some knowledge beforehand is desirable.”

Some of the self-taught and not-taught-at-all people in cannabis testing give the field a bad name in some areas. Nonetheless, Rigdon stands up for the people running these labs. “We need to realize that as an industry, the lab side is only six years old,” she says. “Still, the magnitude of improvement over six years is equal to what we saw in food safety and forensics over a couple decades.”

So, testing cannabis for potency—testing it for anything—remains an industry in development. That is true for the instrumentation and methods, as well as the people running the labs. Even the customers must evolve to understand that the least expensive testing is not always the best. That means that everyone must work together to find the best solutions for this industry.