To produce yeast strains that would reveal the effects of different types of mitochondria on heritability, MIT and Whitehead Institute researchers developed a technique for temporarily fusing yeast cells, letting the mitochondria of one migrate to the other.Collage by Jose-Luis Olivares/MIT; yeast image by Masur/Wikimedia Commons; mitochondria image by Nevit/Wikimedia CommonsIn 2003, when the human genome had been sequenced, many people expected a welter of new therapies to follow, as biologists identified the genes associated with particular diseases.

To produce yeast strains that would reveal the effects of different types of mitochondria on heritability, MIT and Whitehead Institute researchers developed a technique for temporarily fusing yeast cells, letting the mitochondria of one migrate to the other.Collage by Jose-Luis Olivares/MIT; yeast image by Masur/Wikimedia Commons; mitochondria image by Nevit/Wikimedia CommonsIn 2003, when the human genome had been sequenced, many people expected a welter of new therapies to follow, as biologists identified the genes associated with particular diseases.

But the process that translates genes into proteins turned out to be much more involved than anticipated. Other elements — proteins, snippets of RNA, regions of the genome that act as binding sites, and chemical groups that attach to DNA — also regulate protein production, complicating the relationship between an organism’s genetic blueprint, or genotype, and its physical characteristics, or phenotype.

In the latest issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from MIT and the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research argue that biologists trying to explain the connection between genotype and phenotype need to consider yet another factor: genetic material that doesn’t come from an organism’s chromosomes at all.

Through a combination of clever lab experiments and quantitative analysis, the researchers showed that the consequences of deleting genes in yeast cells can’t be explained without the additional consideration of nonchromosomal genetic material — in particular, from the intracellular bodies known as mitochondria and from viruses that can linger in dividing cells.

“This reinforces the idea that when considering human genetics, we need to consider lots of different factors,” says David Gifford, a professor of computer science and engineering at MIT, who led the quantitative analysis. “We need to understand to what extent viruses can be passed from parent to offspring, as well as understanding the spectrum of mitochondria that are present in humans and their potential interactions with chromosomal mutations.”

Benchtop conundrum

The new work grew out of a fairly standard attempt to analyze the role of a particular group of yeast genes, Gifford explains, by comparing the growth rates of yeast colonies in which these genes had or had not been deleted. But the growth of the colonies with deletions was all over the map: Sometimes it was as robust as in the normal yeast cells, sometimes it was dramatically slower, and often it was in between.

“We couldn’t reproduce many of our findings and found out that as experiments were progressing, this double-stranded RNA virus was being lost in particular strains, although it was having a large influence when it was present,” Gifford says. “We then hypothesized that if this virus was important, it was conceivable that other nonchromosomal genetic elements could be important, and that’s when we started looking at the mitochondria. And our collaborators at the Whitehead Institute designed this very clever way of swapping mitochondria between yeast strains so we could isolate and examine exactly what effect the mitochondria were having.”

Mitochondria are an evolutionary peculiarity. Frequently referred to as the “power plant of the cell” because they produce the chemical fuel adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, they are essential components of almost all plant, animal, and fungus cells. But they have their own genomes, which are distinct from those of their host cells. The leading theory about their origin is that they were originally bacteria that developed a symbiotic relationship with early life forms.

Asserting control

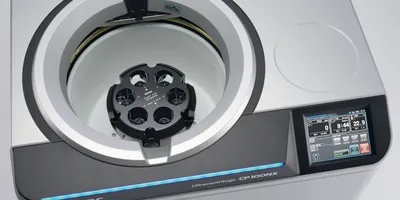

Gerald Fink, the American Cancer Society Professor of Genetics at MIT and a member of the Whitehead Institute, and two researchers in his group — Lindsey Dollard and Anna Symbor-Nagrabska — removed the mitochondria from one of the yeast cells they were studying and allowed it to mate with a cell from a different yeast strain. But they prevented the cells’ nuclei — the repositories of their genetic material — from fusing. Then they forced the new, two-nucleus cell to divide, creating a new strain in which the nucleus of one yeast strain was combined with the mitochondria of the other.

In this way, for each of the genetic deletions the researchers studied, they had strains in which each nuclear state — gene deleted, or left intact — was combined with each of several different types of mitochondria. For each of those strains, they also created variations that were and were not infected with the virus.

Compounded influences

That provided Gifford and his student Matthew Edwards with reliable data, but they still had to make sense of it. Gene deletion alone seemed to explain about 40 percent of the variance they saw in yeast colonies’ growth rates. Gene deletion combined with a blunt categorization of strains according to their nonchromosomal material explained the other 60 percent.

But Gifford and Edwards built a more detailed mathematical model that posited a nonlinear interaction between the virus and particular strains of mitochondria. That model explained more than 90 percent of the variation they saw — not only in colonies with deleted genes, but in the naturally occurring yeast cells as well.

“You might think that the effect of the chromosomal modification and the effect, for example, of the virus were both important but independent,” Gifford says. “What we found is that they weren’t independent. They were synergistic.”

“At a very high level and at a very conceptual level, what they’re showing is that we should also be looking for heritability and variation in phenotype in regions that are not in the chromosomal DNA,” says Eran Segal, a professor of applied mathematics at the Weizmann Institute in Israel whose group does computational biology. “There’s anecdotal evidence that we’ll see similar things in humans.”

Biologists attempting to fill gaps in our understanding of heritability have offered “plausible explanations, like rare variants and combinations that from a statistical-power point of view are hard to analyze,” Segal says. “Some of the missing heritability is definitely in there.” But the MIT researchers’ paper, he says, “highlights that there may be simpler — simpler in the sense that we can more easily access it — heritability that we can explain maybe by also looking at the nonchromosomal genetic material that human cells carry. With fairly easy techniques, we can access that information, and I think that researchers in the field would be wise to begin to look at it.”

To produce yeast strains that would reveal the effects of different types of mitochondria on heritability, MIT and Whitehead Institute researchers developed a technique for temporarily fusing yeast cells, letting the mitochondria of one migrate to the other.

To produce yeast strains that would reveal the effects of different types of mitochondria on heritability, MIT and Whitehead Institute researchers developed a technique for temporarily fusing yeast cells, letting the mitochondria of one migrate to the other.