Eric IsaacsPhoto courtesy of Brookhaven National LaboratoryAs a youth, Eric Isaacs moved from the Midwest to the West Coast. He went from there to the East Coast for his doctoral studies. But he traveled less than 70 miles for his 2013 practicum.

Eric IsaacsPhoto courtesy of Brookhaven National LaboratoryAs a youth, Eric Isaacs moved from the Midwest to the West Coast. He went from there to the East Coast for his doctoral studies. But he traveled less than 70 miles for his 2013 practicum.

Isaacs, a Department of Energy Computational Science Graduate Fellowship (DOE CSGF) recipient, studies applied physics at Columbia University in New York. His practicum was just a couple hours away (in light traffic), at Long Island’s Brookhaven National Laboratory.

For Isaacs, an intellectual bond was more important than physical proximity. "I was interested in forming connections to researchers at Brookhaven and in knowing what's going on there," he says, since it’s packed with experts and high-performance computers.

As a youth, Isaacs lived in a Cleveland suburb, but attended high school near Los Angeles after his father, a surgeon, relocated the family. At the University of California, Berkeley, Isaacs first majored in chemistry, but was frustrated by how little his introductory courses discussed chemical principles' underlying mechanisms. He switched to physics because "it seemed to be the most fundamental way of looking at nature–going down to the lowest level."

This first-principles, or ab initio, approach is key to Isaacs' doctoral research under Chris Marianetti, associate professor of materials science and applied physics and applied mathematics. They develop quantum mechanical models to track how electrons behave in complicated materials, hoping to find compounds that make batteries hold more electricity while absorbing and releasing it efficiently.

"We're using computer simulations to predict, rather than measure directly, properties of materials, particularly properties relevant to actual things you'd want to do with these materials," such as store energy, Isaacs says.

Isaacs' summer project with computational scientist Yan Li was more about explaining materials' properties than predicting them. It arose from experiments at Stony Brook University in New York State, where researchers study cadmium sulfide, a semiconductor. When exposed to sunlight, it acts as a weak photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water. The team found sprinkling a slab of the material with nanoparticles, each made of a few dozen gold atoms at most, increases hydrogen generation by as much as 35 times. They also found platinum, a common catalyst, had a similar effect.

The process could help make hydrogen a clean, plentiful energy source, but it's puzzling. "Gold is an inert noble metal. You think it's not going to be that chemically active," Isaacs says. Exactly why it and platinum (another noble metal) supercharge the reaction is "a big scientific question."

Li, now an editor for the journal Physical Review B, and her team wanted to model interactions between the cadmium sulfide and the nanoparticles. They wanted to calculate how atoms at the interface transfer negative or positive charges and how electron energy levels in the nanoparticles align with those in the substrate.

"Part of the reason we were studying this is for fundamental reasons: to know how we can use these catalysts and nanotechnology to improve this reaction," Isaacs says. "We're really focused on why it works and what's going on at the atomic level."

To get there, Li uses density functional theory (DFT), an ab initio technique that accounts for quantum mechanical conditions in which electrons behave as both particles and waves.

Against the grain

First the models needed to describe how atoms are arranged in the crystalline cadmium sulfide surface. Different arrangements lead to different surface qualities, like structure and charge polarity, that affect interactions with the nanoparticles. It's a bit like how wood cut against the grain differs from wood cut with the grain. Isaacs and Li used the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package, a popular electronic structure code, to model these configurations and compute their properties.

"A crystal has different facets," Li says, and researchers must know which facet is at the surface before simulating it. Experimental data gave few clues as to the correct one "so we had to try ourselves."

Using the Python language, Isaacs wrote a script to cut the simulated cadmium sulfide surface along a crystal orientation. "I didn't teach him anything," Li says. Isaacs studied a software tutorial, then "generated a surface, all by himself. That was very impressive."

Isaacs investigated how rearranging atoms near the surface affects the substrate properties. He researched surfaces with either polar (having nonzero dipole moment–separated positive and negative charges) or nonpolar orientations and probed their electronic properties. For polar cadmium sulfide surfaces, Isaacs examined cases in which the surface terminated with cadmium atoms versus sulfur atoms.

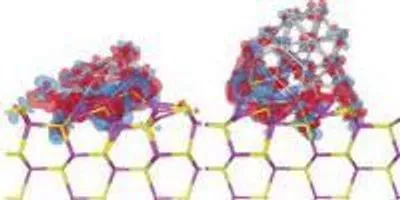

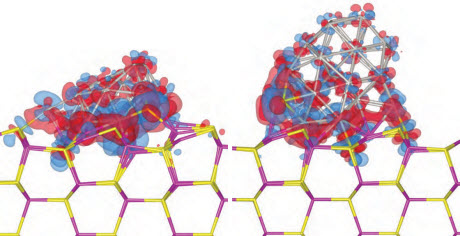

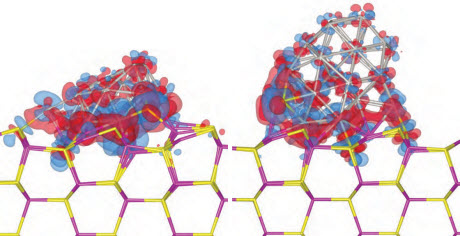

Electron density difference isosurfaces after the adsorption of a 19-atom platinum cluster (left) and a 38-atom platinum cluster (right) on a cadmium sulfide surface. Red and blue denote electron gain and loss, respectively. Image courtesy of Shangmin Xiong, from "Adsorption characteristics and size/shape dependence of Pt clusters on CdS surface," S. Xiong, E. Isaacs and Y. Li, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119 (9), PP 4834-4842.Image courtesy of Berkeley National LaboratoryThe polar surface configuration the researchers tried in an early simulation produced answers that matched poorly with research data. Before the practicum ended, they deduced that a nonpolar molecular orientation works better.

Electron density difference isosurfaces after the adsorption of a 19-atom platinum cluster (left) and a 38-atom platinum cluster (right) on a cadmium sulfide surface. Red and blue denote electron gain and loss, respectively. Image courtesy of Shangmin Xiong, from "Adsorption characteristics and size/shape dependence of Pt clusters on CdS surface," S. Xiong, E. Isaacs and Y. Li, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119 (9), PP 4834-4842.Image courtesy of Berkeley National LaboratoryThe polar surface configuration the researchers tried in an early simulation produced answers that matched poorly with research data. Before the practicum ended, they deduced that a nonpolar molecular orientation works better.

Because it’s arduous to exactly calculate interactions at the cadmium sulfide surface, the team also needed a simplified representation of the noble metal nanoparticles. Isaacs researched the scientific literature to devise one. "It's pretty challenging, if you're not an experimentalist, to make some educated guess on the best model," he adds. "We worked with our experimentalist friends to help out, but there was a lot of digging."

Computations ran at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and on a cluster at Brookhaven's Center for Functional Nanomaterials.

Isaacs is a coauthor on a paper, published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry C, reporting the simulations of platinum nanoparticles on a nonpolar surface. The first author, Stony Brook graduate student Shangmin Xiong, did much of the work, Li says, but Isaacs "really helped to kick-start the project." He knew the theory behind the models and already was familiar with the computer codes to run them. "It only took a couple days to let him start doing some calculations," Li says. "This was definitely a happy surprise."

Results indicate that nanoparticle size greatly influences the water-splitting effect, Li says, but it's unclear which works best with the surface to promote the reaction. Simulations can help unravel this, but they'll require more detailed - and demanding - approaches, she adds.

Isaacs presented a poster on the practicum work at a Brookhaven Young Researcher Symposium in November 2013. Marianetti says the experience "widened (Isaacs') view by pushing him into an area of problems that he wouldn't have seen in my research group."

Making a transition

That perspective could help as Isaacs investigates materials containing transition metals: elements with partially filled electron shells, allowing them to easily receive and donate electrons - a key battery cathode material property.

Most transition metal compounds in cathodes are oxides, with the metal coupled to oxygen atoms. Many already are in devices like cellphones. But numerous transition metal oxides are strongly correlated materials–"notoriously difficult to understand" substances, Isaacs says. "To go beyond the current technology and even just to better understand how it works, we need to improve our descriptions of strongly correlated materials and to predict properties of new ones."

DFT maps the many-body problem, in which every electron interacts with every other electron, onto an easier, non-interacting electron problem. But in strongly correlated materials, some electrons interact intimately. "Because of that, it's very difficult, or in some sense impossible in practice, to model the material at a level that considers just single electrons," as DFT does, Isaacs says.

Take, for example, lithium iron phosphate, a promising battery material Isaacs studies. DFT, Marianetti says, "claims you should be able to diffuse lithium in and out and it should mix" as the battery charges. Experiments show just the opposite: It separates into phases of iron phosphate and lithium iron phosphate, limiting how fast the battery can charge and discharge.

To understand this and other strongly correlated materials, Marianetti's group combines DFT with dynamical mean field theory (DMFT). It calculates electron interactions more explicitly, but can't cope with a huge number. Instead, it calculates strongly correlated interactions while DFT accounts for the rest.

Marianetti says his group has worked on combining DMFT and DFT, but "Eric is pushing forward toward actually applying this to battery materials, which would be sort of a massive leap."

It's a perfect subject, Isaacs adds: "We're looking at questions of basic science, but we’re also looking at a technologically relevant material in hopes this can make an impact."

In his off hours, Isaacs sometimes makes a different kind of impact: punching an opponent in the boxing ring. "It's good exercise," he says, and "very helpful to reset after so much of reading papers and coding."

Isaacs aims to knock out his doctorate sometime in 2016. Regardless of where he works, he wants to connect his research with everyday products that improve life.

After all, "the battery in the cellphone I'm using right now was only an idea in a lab not long ago."

Stretching to a surprising research result

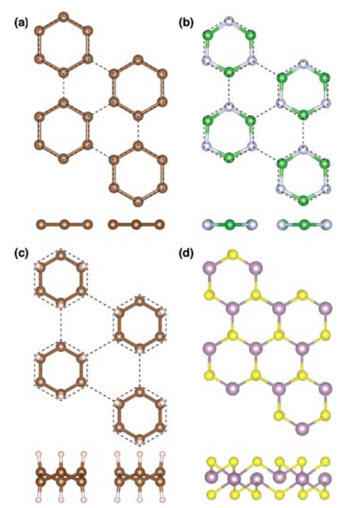

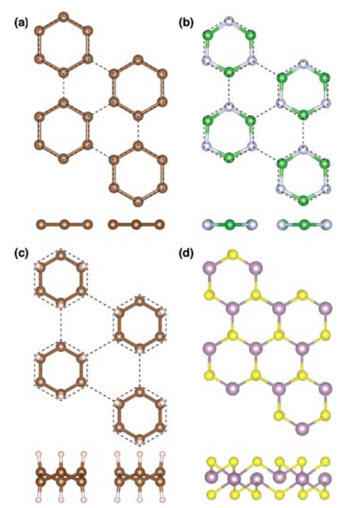

Projections from the top and side of distorted structures for (a) graphene, (b) boron nitride, (c) graphane and (d) molybdenum disulfide each strained equally in all directions. The carbon, boron, nitrogen, hydrogen, molybdenum and sulfur atoms are represented as brown, green, silver, white, purple and yellow spheres, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the undistorted strained lattice. In graphene, boron nitride and graphane the backbone distorts toward isolated six-atom rings, while molybdenum disulfide undergoes a distinct distortion toward trigonal pyramidal coordination. Reprinted with permission from E.B. Isaacs and C.A. Marianetti, Phys. Rev. B 89, 184111 (2014).Image courtesy of Brookhaven National LaboratoryThe project Eric Isaacs took as he joined Chris Marianetti's materials science and engineering group proved more interesting than a mere exercise to learn new techniques.

Projections from the top and side of distorted structures for (a) graphene, (b) boron nitride, (c) graphane and (d) molybdenum disulfide each strained equally in all directions. The carbon, boron, nitrogen, hydrogen, molybdenum and sulfur atoms are represented as brown, green, silver, white, purple and yellow spheres, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the undistorted strained lattice. In graphene, boron nitride and graphane the backbone distorts toward isolated six-atom rings, while molybdenum disulfide undergoes a distinct distortion toward trigonal pyramidal coordination. Reprinted with permission from E.B. Isaacs and C.A. Marianetti, Phys. Rev. B 89, 184111 (2014).Image courtesy of Brookhaven National LaboratoryThe project Eric Isaacs took as he joined Chris Marianetti's materials science and engineering group proved more interesting than a mere exercise to learn new techniques.

The subject was monolayer materials: sheets between one and a few atoms thick that are remarkably strong and have unusual properties. In a previous study, Marianetti's group found that graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms, underwent a surprising transition as it broke under stress. He suggested Isaacs see what happens to other monolayers under similar conditions.

Using Brookhaven National Laboratory supercomputers, Isaacs modeled graphene, boron nitride, molybdenum disulfide and graphane (graphene in which each carbon atom bonds with a hydrogen atom). Many such monolayers are built of six-atom backbones linked like a hexagon. The simulations stretched the sheets equally in all directions.

In monolayer materials, as in all substances, atoms rapidly vibrate in place. In most cases, stretching leads to elastic instability, in which atomic bonds continuously break and the material separates uniformly.

Isaacs' models indicate that monolayer materials' vibrational modes change under stress. "There's a subtle instability that happens" instead of elastic instability, he says. "The material will not just start vibrating in that mode and return to equilibrium, but will keep going," essentially transforming into a new structure. In this "soft mode" the molecules tend to separate into isolated hexagons.

In an elastic instability model, the new structure will break by that point. "In these calculations, we're not seeing the actual breaking process, but we're predicting when it would happen and what the mechanism is." It turns out this change from the beginning vibrational mode into another unstable structure limits the materials' strength.

This instability was unexpected, but it was more surprising that all the materials were susceptible despite their different electronic properties. Isaacs "generalized this for most of the monolayer materials," Marianetti says. "What he showed, which was not obvious, is that most of them shared a very similar, if not identical, instability. It was

beautiful work."

The results could help researchers better predict the strain a material can take and find ways to delay or overcome this soft mode to strengthen substances.