Laboratories face increasing demand for rapid, high-precision soil data to support precision agriculture. Integrating remote sensing, drones, and soil analyzers allows facilities to expand capabilities beyond traditional wet chemistry methods. These technologies streamline workflow, reduce sample backlog, and provide comprehensive geospatial contexts for analytical results. While traditional benchtop analysis remains the gold standard for regulatory compliance, the incorporation of field-generated data creates a hybrid model of analysis. This approach improves turnaround times and offers clients a multi-dimensional view of soil health. The following sections explore how these innovations intersect with standard laboratory operations.

Remote sensing technologies enhance soil characterization

Remote sensing technologies capture spectral data that correlates with specific soil properties, offering a macro-level view that complements micro-level benchtop analysis.

Traditional soil sampling often relies on grid or zone methodologies, which can miss variability between collection points. Remote sensing addresses this spatial gap by utilizing sensors mounted on satellites or aircraft to measure electromagnetic radiation reflected or emitted from the soil surface. This data provides laboratories with a continuous layer of information regarding soil organic matter (SOM), moisture content, and salinity levels.

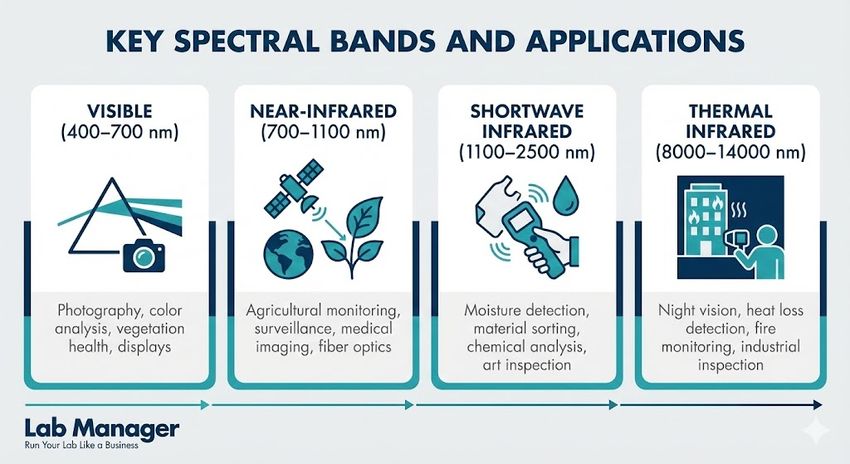

Optical remote sensing utilizes visible (VIS), near-infrared (NIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands. Soil chromophores—materials that absorb light—interact with these bands distinctively. For instance, soil organic carbon exhibits specific spectral absorption features in the VIS-NIR region. By analyzing these spectral signatures, laboratory professionals can create predictive models that estimate carbon stocks across vast areas without processing thousands of physical samples.

Thermal infrared remote sensing proves particularly useful for moisture analysis. Variations in soil surface temperature, driven by thermal inertia and evaporative cooling, correlate strongly with water content. This data aids laboratories in normalizing results based on field conditions at the time of sampling.

Key spectral bands and applications:

Mapping the Spectrum: Key Bands and Their Analytical Applications

GEMINI (2025)

- Visible (400–700 nm): Iron oxide content and soil color classification.

- Near-Infrared (700–1100 nm): Organic matter estimation and vegetative cover interference.

- Shortwave Infrared (1100–2500 nm): Clay mineralogy identification and moisture quantification.

- Thermal Infrared (8000–14000 nm): Surface temperature mapping and irrigation planning.

Research published in Remote Sensing of Environment indicates that combining spectral indices with laboratory calibration samples significantly reduces the root mean square error (RMSE) of soil property maps. This synergy ensures that the remote data remains grounded in analytical reality.

Drones automate soil sampling and data collection

Drones equipped with advanced sensors and sampling mechanisms provide laboratories with consistent, spatially accurate sample collection methods.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, serve as the physical link between remote sensing and laboratory analysis. Unlike satellites, which may suffer from cloud cover interference or low temporal resolution, drones offer on-demand deployment. For laboratory professionals, the value of drone technology lies in two distinct areas: high-resolution proximal sensing and physical sample retrieval.

Proximal sensing involves mounting miniaturized hyperspectral or LiDAR sensors onto the UAV. These sensors fly at low altitudes, capturing data with centimeter-level precision. This granularity reveals soil heterogeneity that satellite imagery might blur. For example, LiDAR systems can map micro-topography, which dictates water flow and nutrient leaching. Understanding these physical parameters helps laboratory managers interpret anomalous chemical results from specific zones.

Recent innovations have introduced drones capable of physical soil interaction. These heavy-lift UAVs carry automated augers or core samplers. They fly to pre-determined GPS coordinates, extract a soil core, and transport it to a central collection hub or directly to a mobile field lab. This automation reduces human error associated with sampling depth and handling. It ensures that the sample arriving at the laboratory bench represents the exact location specified in the sampling plan.

Lab Quality Management Certificate

The Lab Quality Management certificate is more than training—it’s a professional advantage.

Gain critical skills and IACET-approved CEUs that make a measurable difference.

Comparison of manual vs. drone-assisted sampling:

Feature | Manual Sampling | Drone-Assisted Sampling |

|---|---|---|

Consistency | High variability between samplers | Programmed, mechanical consistency |

Accessibility | Limited by terrain and crop height | Capable of reaching difficult terrain |

Geolocating | GPS handheld (3–5m accuracy) | RTK-GPS integration (<1cm accuracy) |

Throughput | Labor-intensive and slow | Rapid deployment and collection |

Contamination | Potential for cross-contamination | Automated sterilization protocols |

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the United States and similar bodies globally regulate these operations. Adherence to Part 107 regulations ensures that drone operations remain safe and compliant while supporting laboratory logistics.

Portable soil analyzers streamline laboratory workflows

Portable X-ray fluorescence and laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy units allow technicians to perform immediate elemental analysis in the field.

The miniaturization of analytical instrumentation has brought laboratory-grade technology directly to the field. Handheld X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF) and Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) are the primary tools in this category. These devices do not replace the Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) or Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) found in the central lab, but they serve as powerful screening and triage tools.

pXRF analyzers work by ionizing atoms with X-rays, causing them to emit fluorescent energy characteristic of specific elements. This technique is highly effective for detecting heavy metals (such as lead, arsenic, and cadmium) and micronutrients (such as iron, zinc, and copper). For an environmental laboratory, pXRF allows for the rapid delineation of contamination hotspots. Only samples requiring certified quantification or legal defensibility then need transport to the brick-and-mortar facility. This reduces the analytical load on expensive benchtop instruments and saves reagents.

LIBS technology creates a micro-plasma on the sample surface using a high-energy laser. As the plasma cools, it emits light at specific wavelengths. LIBS is particularly adept at detecting light elements that pXRF struggles with, including carbon, nitrogen, and magnesium. Recent advancements have improved the detection limits of LIBS, making it a viable tool for in-field nutrient profiling.

Operational considerations for portable analyzers:

- Sample Preparation: Field moisture significantly attenuates XRF signals. Drying or correcting for moisture factor is essential.

- Matrix Effects: Soil particle size and heterogeneity affect reproducibility. In-situ analysis yields qualitative data, while ex-situ preparation (grinding/sieving) improves quantitative accuracy.

- Regulatory Acceptance: Method 6200 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) validates the use of Field Portable XRF for screening, establishing its legitimacy in professional workflows.

Integrating remote sensing and soil analyzers in agrilabs

Advanced software ecosystems now link field data from sensors directly into laboratory information management systems for holistic reporting. Agricultural laboratories (agrilabs) act as the central hub where field innovations converge with analytical rigor. The influx of data from remote sensing, drones, and soil analyzers requires robust digital infrastructure to ensure traceability and accuracy. Modern agrilabs are adopting cloud-based platforms that ingest geospatial data from drones and correlate it with benchtop analyzer results. This synthesis allows for the generation of variable rate application maps that are far more precise than those derived from grid sampling alone. By validating remote data with wet chemistry, agrilabs maintain their status as the gold standard for compliance and recommendation generation.

This integration presents challenges and opportunities regarding data integrity. A drone-collected spectral image is a dataset, just as an ICP-MS readout is a dataset. Merging these requires sophisticated Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) capable of handling geospatial file formats (like GeoTIFF) alongside tabular chemical data.

Interoperability allows for "smart sampling." Instead of a static grid, the remote sensing data directs the sampling plan. The drone identifies an area of spectral stress, and the LIMS triggers a work order for physical sampling in that specific zone. The physical sample is analyzed, and the results calibrate the remote sensing model for the rest of the field. This feedback loop enhances the value of the laboratory, transforming it from a simple testing facility into an agronomic data center.

Future soil testing relies on remote sensing, drones, and soil analyzers

The convergence of remote sensing, drones, and soil analyzers creates a robust analytical ecosystem that extends the laboratory's reach. By leveraging spectral data from satellites and UAVs, laboratories can contextualize point-source data within a broader spatial framework. The deployment of handheld analyzers streamlines sample intake, ensuring that high-precision benchtop instruments focus on the most critical samples. Ultimately, the adoption of these technologies enables laboratory professionals to deliver faster, more actionable insights to the agricultural sector while maintaining the scientific standards required for regulatory compliance.

FAQ

How does remote sensing improve soil testing accuracy?

Remote sensing improves accuracy by identifying spatial variability across a field, ensuring that physical samples represent distinct soil zones rather than arbitrary grid points. It provides a continuous data layer that helps laboratories interpolate point data more effectively.

Are handheld soil analyzers as accurate as benchtop instruments?

Handheld soil analyzers are generally less sensitive than benchtop instruments like ICP-MS, particularly at trace detection levels. However, when properly calibrated and used for screening or macro-nutrient analysis, they offer sufficient accuracy for immediate decision-making and hotspot delineation.

What regulations apply to using drones for soil sampling?

Drone operations for commercial purposes, including soil sampling, generally fall under aviation authority regulations, such as the FAA Part 107 in the United States. These rules govern pilot certification, line-of-sight requirements, and maximum altitude restrictions.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.