Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan have developed fully autonomous robots smaller than a grain of salt, demonstrating how sensing, computation, and movement can be integrated at microscopic scales. While the technology is not intended for immediate laboratory deployment, it highlights emerging approaches to automation and microscale sensing that could influence future laboratory platforms and experimental design.

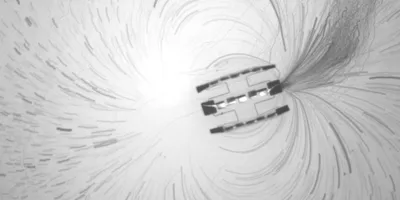

The light-powered robots measure approximately 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers and operate in liquid environments without external control. At this scale, traditional robotic designs fail due to dominant forces such as drag and viscosity. By enabling autonomous operation under these constraints, the researchers established a new technical framework for devices designed to function inside microenvironments commonly encountered in laboratory research.

How microscopic autonomous robots move and operate

Rather than relying on motors or mechanical parts, microscopic autonomous robots move by generating localized electric fields. These fields push charged ions in the surrounding liquid, which in turn carry nearby fluid molecules and propel the robot forward. By adjusting the electric field, the robots can change direction, follow complex paths, and coordinate movement with nearby robots.

This propulsion method is well-suited to microscale environments, where fragile moving parts are prone to failure. Because the robots contain no mechanical actuators, they can withstand repeated handling and extended operation. Powered by LED light, they can operate continuously for months, an important consideration for long-duration laboratory experiments.

Integrating microscale sensing and computation

True autonomy requires more than motion. Each robot integrates a microscopic computer with a processor, memory, and temperature sensors, all powered by tiny solar cells that produce extremely limited energy. To operate within these constraints, the research team redesigned both hardware and software to reduce power consumption by orders of magnitude.

The robots can detect temperature changes as small as one-third of a degree Celsius, enabling microscale sensing within liquid environments. Instead of transmitting data wirelessly, measurements are encoded into subtle movement patterns that can be recorded using microscopy and decoded during analysis. This unconventional communication method reflects the design tradeoffs required at such small scales.

What this research signals for lab managers and laboratory automation

For lab managers, the significance of microscopic autonomous robots lies in what they signal about the future direction of laboratory automation rather than immediate adoption. The research demonstrates that sensing, computation, and decision-making can be embedded directly into microenvironments, rather than remaining centralized in instruments or external control systems.

As laboratory automation continues to evolve, similar design principles are already appearing in larger platforms, including embedded intelligence, reduced manual intervention, and software-driven experimentation. Microscopic autonomous robots represent an extreme example of these trends, offering a preview of how future laboratory tools may operate inside samples, microfluidic devices, or lab-on-a-chip systems.

The development is not expected to affect laboratory purchasing decisions, compliance requirements, or staffing models in the near term. Instead, it establishes a research platform that illustrates the continued convergence of robotics, electronics, and life sciences at increasingly small scales. For laboratory leadership, tracking such advances supports informed awareness of emerging approaches that may influence experimental methods and automation strategies over time, even as practical applications remain several years away.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.