The rheological properties of injectable drugs determine the formulation's stability, manufacturability, and ease of administration to the patient. Laboratory professionals must characterize these flow behaviors early in development to ensure that high-concentration biologics and complex suspensions meet rigorous quality standards. Understanding the relationship between shear rate and viscosity allows scientists to predict how a drug will perform during the high-shear process of injection.

Why rheological characterization ensures injectable drug stability

Rheological characterization provides the quantitative data necessary to predict how a drug product will behave under the varying stress conditions of manufacturing and clinical use. Injectable drugs endure a wide range of shear rates, from near-zero shear during storage to extremely high shear rates during needle passage. Mapping the rheological profile across these regimes prevents failures such as needle clogging, phase separation, or unacceptably high injection forces.

Flow properties directly influence the bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profile of subcutaneous and intramuscular injections. If a formulation exhibits excessive viscosity or unexpected viscoelasticity, the drug depot may not spread or diffuse into the tissue as intended. This can lead to variability in absorption rates and potentially alter the therapeutic effect.

Manufacturing processes rely heavily on consistent rheological properties to maintain throughput and dosage accuracy. Pumping, mixing, filtration, and filling operations all impose mechanical stress on the fluid. Variations in flow behavior can cause line stoppages, inaccurate fill volumes, or degradation of shear-sensitive active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

Rheology is more than just measuring flow; it is a critical predictor of a product's real-world performance.

GEMINI (2026)

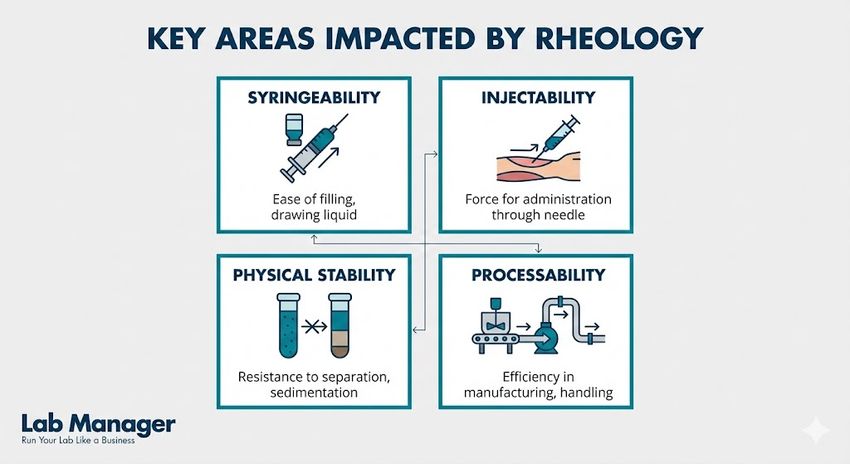

Key areas impacted by rheology:

- Syringeability: The ability of a solution to be drawn into a syringe from a vial (suction).

- Injectability: The force required to expel the drug through a specific needle gauge (expulsion).

- Physical Stability: The resistance of a suspension or emulsion to sedimentation or creaming over time.

- Processability: The efficiency of fluid transport during aseptic manufacturing and fill-finish operations.

Analyzing non-Newtonian flow behavior in biologics

Most simple aqueous solutions behave as Newtonian fluids, where viscosity remains constant regardless of the applied shear rate. However, complex injectable drugs—particularly monoclonal antibodies, protein therapeutics, and colloidal suspensions—frequently exhibit non-Newtonian behavior. Identifying the specific type of non-Newtonian flow is essential for designing appropriate delivery systems.

Shear-thinning (pseudoplastic) behavior is the most common non-Newtonian profile observed in pharmaceutical formulations. In shear-thinning fluids, viscosity decreases as the shear rate increases. This property is advantageous for injectables because the formulation remains stable and viscous in the vial (low shear) but flows easily through the hypodermic needle (high shear).

Yield stress is another critical parameter for suspension-based injectables and depot formulations. A fluid with a yield stress acts as a semi-solid at rest and only begins to flow once a specific threshold of stress is applied. This property helps maintain the suspension of particles during storage, preventing hard caking at the bottom of the vial.

Common non-Newtonian behaviors in injectables:

Behavior Type | Description | Relevance to Injectables |

|---|---|---|

Pseudoplasticity | Viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate. | Reduces injection force; improves patient comfort. |

Dilatancy | Viscosity increases with increasing shear rate. | Can cause needle blockage; generally undesirable. |

Thixotropy | Viscosity decreases over time under constant shear. | Impacts recovery time after injection; affects depot formation. |

Viscoelasticity | Material exhibits both viscous and elastic characteristics. | Critical for hydrogels and tissue implants. |

Laboratory professionals utilize rotational rheometers and micro-capillary viscometers to differentiate these behaviors. By generating a flow curve (viscosity vs. shear rate), scientists can determine if a formulation will require a larger needle gauge or a specialized autoinjector mechanism.

Measuring injectability and syringeability for optimal delivery

Injectability and syringeability are functional metrics derived directly from the fundamental rheological properties of the formulation. While rheology describes the intrinsic material properties, injectability measurements quantify the system performance, incorporating the device geometry and friction.

The glide force, or the force required to maintain the movement of the plunger, is heavily dependent on the dynamic viscosity of the drug product at high shear rates. As the fluid is forced through the narrow cannula of a needle, shear rates can exceed 100,000 reciprocal seconds (1/s). Rheological data extrapolated from low-shear measurements often fails to predict behavior at these extremes, necessitating high-shear viscometry.

The break-loose force is the initial force required to initiate the movement of the plunger. This value is influenced by the static friction of the syringe stopper and the yield stress of the formulation. High break-loose forces can cause "dose dumping," where the sudden release of pressure leads to a rapid, painful injection.

Factors influencing injection force:

- Needle Geometry: Injection pressure scales inversely with the fourth power of the needle radius (Hagen-Poiseuille law), drastically impacting force.

- Viscosity: Force increases linearly with the dynamic viscosity of the fluid.

- Injection Speed: Faster injection rates generate higher shear and require greater force.

- Temperature: Cold storage increases viscosity, significantly raising the required injection force.

To optimize these parameters, formulators often employ excipients that modify the rheological profile without compromising drug stability. For example, adding specific salts or amino acids can disrupt protein-protein interactions that cause high viscosity in concentrated antibody solutions.

How temperature affects viscosity and injectable drug delivery

Temperature fluctuations significantly alter the rheological properties of injectable drugs, affecting both storage stability and administration. Since many biologics require cold chain storage (2°C to 8°C), the viscosity of the formulation at the time of injection may be considerably higher than at room temperature.

The Arrhenius equation describes the relationship between temperature and viscosity for Newtonian fluids, where viscosity decreases as temperature rises. However, for complex non-Newtonian systems containing proteins or polymers, the temperature dependence can be non-linear and unpredictable. A formulation that flows easily at 25°C may become unacceptably viscous or even gel-like at refrigerated temperatures.

Instructions for use often recommend equilibrating the drug to room temperature before administration to mitigate this issue. If a patient injects a cold formulation, the increased viscosity leads to higher injection forces and perceived pain. Laboratory testing must therefore characterize rheological profiles across the entire relevant temperature range, from storage conditions to body temperature.

Thermodynamic instability at elevated temperatures can also lead to irreversible rheological changes. Protein denaturation or aggregation induced by heat often results in a permanent increase in viscosity. Rheological assays serve as sensitive indicators of early-stage aggregation, detecting changes in flow behavior before visible precipitation occurs.

Critical temperature checkpoints for rheology testing:

- Storage Temperature (2°C–8°C): Assesses viscosity for syringeability immediately upon removal from refrigeration.

- Room Temperature (20°C–25°C): Represents the standard condition for administration.

- Body Temperature (37°C): Relevant for understanding drug spreading and depot formation post-injection.

- Stress Testing (>40°C): Used in accelerated stability studies to predict degradation.

Regulatory guidelines for rheological assessment of injectables

Regulatory bodies, including the FDA and EMA, expect comprehensive rheological data as part of the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) for injectable drugs. Under the Quality by Design (QbD) framework, rheology is considered a Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) for any formulation where flow behavior impacts dosing accuracy or manufacturability.

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) provides general chapters guiding these measurements. Key chapters include USP <912> Rotational Rheometer Methods, and USP <911> Viscosity—Capillary Methods. and USP <1791> Rheology. Adherence to these standards ensures that data is generated using validated methods and calibrated instrumentation.

For generic parenteral products, demonstrating rheological equivalence to the reference listed drug (RLD) is often mandatory. If the test product exhibits a different flow profile—such as being Newtonian while the reference is shear-thinning—it may not be considered bioequivalent, particularly for depot or topical ophthalmic formulations.

Reproducibility of rheological measurements is a common scrutiny point during regulatory review. Laboratory professionals must control variables such as sample history, loading technique, and thermal equilibrium time. For thixotropic fluids, the history of shear applied to the sample before testing can drastically alter the results, requiring strict standardization of sample preparation protocols.

High-concentration protein formulations: High-concentration protein formulations (HCPFs) present unique rheological challenges due to the dense packing of macromolecules in solution. When protein concentrations exceed 100 mg/mL, intermolecular distances decrease, leading to strong protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that cause an exponential increase in viscosity. This phenomenon complicates the delivery of subcutaneous biologics, which often require small volumes (1–2 mL) to be delivered in a short time. To mitigate high viscosity, formulators utilize rheology modifiers and viscosity-reducing excipients like arginine or histidine to screen electrostatic charges and reduce PPI network formation. Accurate rheological characterization of HCPFs requires specialized microfluidic viscometers capable of measuring small sample volumes at the ultra-high shear rates characteristic of injection, ensuring that the formulation remains deliverable within the force limits of standard autoinjectors.

Leveraging rheological data for successful drug development

Characterizing the rheological properties of injectable drugs is a fundamental requirement for ensuring product quality, stability, and clinical efficacy. By rigorously mapping viscosity, viscoelasticity, and yield stress, scientists can optimize formulations to withstand the rigors of manufacturing and delivery.

A robust rheological control strategy minimizes the risk of batch failures and ensures consistent patient experiences. As injectable therapies become more complex, advanced rheological analysis remains the primary tool for bridging the gap between molecular formulation and successful drug delivery.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.