Precision in lab operations often hinges on the accurate characterization of fluid behavior. specifically viscosity and rheology, which dictate how materials deform and flow under stress. In the competitive landscape of modern material science and manufacturing, understanding these properties is no longer optional. It is a critical component for validating formulation stability, ensuring processability, and meeting stringent regulatory standards across industries.

These standards apply to sectors ranging from pharmaceuticals to petrochemicals. While viscosity measures a fluid's resistance to flow at a single condition, it provides only a snapshot of material behavior. In contrast, rheology offers a comprehensive motion picture. It details deformation under varying shear rates, timescales, and temperatures.

Mastering these concepts allows laboratories to enhance data integrity and optimize production scaling. It also helps maintain the highest levels of quality assurance. Ultimately, this knowledge prevents costly batch failures and ensures end-user safety.

Defining Viscosity and Rheology Fundamentals for Lab Operations

At the heart of fluid dynamics in a laboratory setting lies the distinction between simple flow resistance and complex deformation behavior. Viscosity represents the internal friction of a fluid. It essentially quantifies its thickness or resistance to pouring. In routine lab operations, this measurement is often sufficient for Newtonian fluids.

Newtonian fluids include materials like water, simple oils, and dilute solvents. Their viscosity remains constant regardless of the speed at which they are sheared. However, the majority of modern engineered materials exhibit non-Newtonian behavior. For these materials, the resistance to flow changes dramatically depending on the applied force.

This is where rheology becomes indispensable. It provides the analytical depth required to characterize complex fluids that defy simple linear definitions. Rheology extends beyond simple viscosity to analyze critical parameters such as viscoelasticity, yield stress, and thixotropy. For instance, a material might act like a solid at rest to maintain suspension stability.

Yet, that same material must flow like a liquid under the pressure of a pump. Laboratory professionals must distinguish between dynamic viscosity and kinematic viscosity. Dynamic viscosity is measured in Pascal-seconds (Pa·s). Kinematic viscosity is measured in Stokes (St) and accounts for the fluid's density.

Table 1: Comparison of Viscosity vs. Rheology in Lab Contexts

Feature | Viscosity | Rheology |

|---|---|---|

Primary Measurement | Resistance to flow (Internal Friction) | Deformation and flow under stress |

Data Output | Single point value (typically) | Flow curves, viscoelastic modulus |

Ideal Sample Type | Newtonian fluids (Water, Oils) | Non-Newtonian / Complex fluids (Gels, Pastes) |

Operational Focus | Quality Control (Pass/Fail) | R&D, Formulation, Process Simulation |

Key Variable | Temperature | Shear Rate, Shear Stress, Time, Temperature |

Accurate conversion between these metrics is critical when comparing results from different instruments. For example, comparing capillary viscometers used for dilute solutions against rotational rheometers used for structured gels requires careful calculation. Furthermore, understanding the distinctions between shear stress-controlled and shear rate-controlled experiments is vital. This allows researchers to better mimic real-world processing conditions.

These conditions range from high-speed mixing to slow gravity-driven leveling. Temperature control serves as another pillar of reliable measurement in rigorous lab operations. Since viscosity is inversely proportional to temperature for most liquids, even minor fluctuations can skew results significantly. A change of just 1°C can alter viscosity data by up to 10% for certain oils.

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) must mandate precise temperature regulation. This often involves using advanced Peltier plates or fluid jackets capable of maintaining stability within ±0.01°C. This precision ensures that data remains comparable across different batches and testing sites. When characterizing novel polymers or biological samples, understanding the thermal history of the sample is equally important.

Heating and cooling cycles can induce irreversible structural changes. These changes, such as cross-linking or denaturation, permanently alter the rheological profile.

Whether you are formulating new products or conducting quality control, understanding flow behavior is critical.

GEMINI (2026)

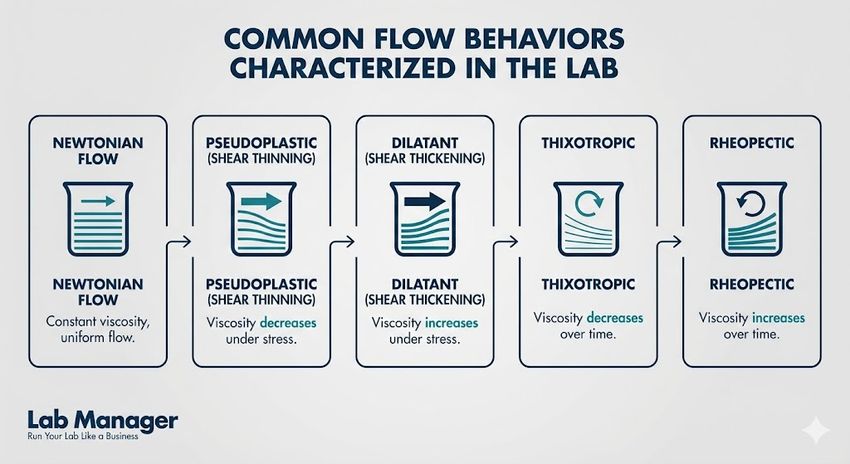

Common Flow Behaviors Characterized in the Lab

- Newtonian Flow: Viscosity remains constant regardless of shear rate (e.g., Water, Silicone Oil).

- Pseudoplastic (Shear Thinning): Viscosity decreases as shear rate increases (e.g., Paint, Ketchup, Blood).

- Dilatant (Shear Thickening): Viscosity increases as shear rate increases (e.g., Cornstarch in water).

- Thixotropic: Viscosity decreases over time under constant shear (e.g., Yogurt, Gels).

- Rheopectic: Viscosity increases over time under constant shear (rare, e.g., Synovial fluid).

Rheology of Injectable Drugs: Ensuring Delivery and Stability

The application of rheology is perhaps most critical in the pharmaceutical sector. It is particularly vital concerning the development of injectable drugs. Modern biologics and high-concentration protein formulations frequently exhibit complex, non-Newtonian behavior. This behavior challenges traditional delivery methods.

Laboratory professionals utilize rheological profiling to predict "syringeability" and "injectability." Syringeability refers to the force required to expel a drug from a syringe. Injectability refers to the performance of the formulation during the injection process into tissue. High viscosity at high shear rates can impede administration.

This resistance can cause patient discomfort and potential non-compliance. Furthermore, unstable rheological properties might indicate protein aggregation, unfolding, or denaturation. Rheometers provide crucial data by simulating extremely high shear rates. These rates often exceed 100,000 s⁻¹ inside a narrow hypodermic needle.

Key Parameters for Injectable Drug Analysis:

- Zero-Shear Viscosity: Indicates stability in the vial during storage.

- High-Shear Viscosity: Predicts flow through the needle during administration.

- Yield Stress: Determines the force required to initiate flow.

- Viscoelastic Modulus (G' and G''): Assessing the gel-like structure vs. liquid-like behavior.

This data ensures the therapeutic efficacy and safety of parenteral therapies. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA increasingly emphasize the comprehensive characterization of these flow properties. Their goal is to guarantee lot-to-lot consistency and patient safety.

Food Quality Control: Optimizing Texture via Rheology

Similarly, food quality control relies heavily on textural analysis derived from detailed rheological data. The consumer's sensory experience is a direct function of flow properties. This includes the mouthfeel of a beverage, the spreadability of butter, and the creaminess of yogurt. In these lab operations, yield stress is a vital parameter.

Yield stress determines whether a suspension will hold particles in suspension. For example, a salad dressing must hold herbs, and chocolate milk must suspend cocoa particles. Without sufficient yield stress, these products settle into an unappealing sludge. Rheological testing helps food scientists formulate products that maintain their structure.

They must withstand the mechanical stress of transport and storage. However, they must also break down pleasantly during mastication. Furthermore, tribology is often coupled with rheology in food labs. Tribology is the study of friction and lubrication.

This combination helps researchers understand how fluids interact with oral surfaces. It guides the development of low-fat alternatives that retain the "creamy" feel of full-fat counterparts.

Table 2: Correlating Rheology to Sensory Attributes

Rheological Property | Sensory Attribute | Consumer Perception | Product Example |

|---|---|---|---|

Yield Stress | Stability / Spoonability | "Thick" or "Rich" | Mayonnaise, Greek Yogurt |

Viscosity at 50 s⁻¹ | Mouthfeel / Swallowing | "Creamy" vs "Watery" | Nutritional Shakes, Soups |

Thixotropy | Structure Recovery | "Body" after stirring | Ketchup, Gelatin Desserts |

Tan Delta (Damping) | Gel Strength | "Chewy" vs "Mushy" | Cheese, Gummy Candies |

Forensic Materials Analysis: Rheology in Investigation

Beyond consumer goods, forensic materials also demand rigorous rheological scrutiny. Rheology serves as a silent witness in criminal investigations. In bloodstain pattern analysis, the non-Newtonian nature of blood is key. Specifically, its shear-thinning behavior dramatically affects how it disperses upon impact.

It also dictates how droplets form during flight. Forensic laboratories use rheology to model droplet formation and drying kinetics. This aids in the accurate reconstruction of crime scenes. Understanding how blood changes viscosity as it clots, dries, and ages provides investigators with a timeline.

It creates a physical model of events. Additionally, the rheology of other forensic evidence can be fingerprinted. This includes soil traces or polymer-based adhesives found at a scene. These rheological fingerprints can link suspects to specific locations or materials.

Inline Rheology Monitoring for Enhanced Reproducibility

Data reliability is a perennial challenge in scientific research. This makes reproducibility a top priority for laboratory managers and principal investigators. Inconsistent sample handling can lead to highly variable results. Specifically, the shear history of a sample before it enters the measurement gap is a major variable.

These inconsistencies can undermine confidence in the data. Automated sample loading and standardized pre-shear protocols on modern rheometers help mitigate these human errors. They ensure every sample starts from the same thermodynamic and structural state. Furthermore, the integration of inline rheology monitoring is transforming operations.

It changes how lab operations interface with pilot production and scale-up. Instead of extracting samples for offline testing, inline process viscometers provide continuous data. Offline testing introduces time delays and potential temperature changes. It also risks sample degradation.

Benefits of Inline Rheology Monitoring:

- Real-time Feedback: Immediate data stream allows for instant process adjustment.

- Elimination of Sampling Error: Removes variables introduced during sample extraction and transport.

- Process Optimization: Identifies the exact endpoint of mixing or reaction.

- Waste Reduction: Prevents the production of off-spec batches.

This immediate feedback loop allows operators to adjust mixing speeds. They can also tune pump pressures or temperatures instantly. This ensures the final product stays within strict specifications.

Safety Protocols for Measuring Hazardous Fluids

Safety protocols regarding hazardous fluids have also driven significant innovation in rheological measurement hardware. When testing volatile solvents or radioactive materials, risks are high. Carcinogenic compounds or biohazardous samples also pose threats. Traditional open-system testing poses significant risks to personnel through inhalation or contact.

Modern lab operations employ hermetically sealed cell systems. They also use magnetic coupling drivers to isolate the sample from the environment completely. This containment is crucial for operator safety. It is also vital for maintaining the compositional integrity of the sample.

Sealing prevents solvent evaporation that would artificially increase viscosity readings. Such evaporation would lead to erroneous data. These specialized fixtures often include fume hood integration capabilities. Remote operation features further distance the analyst from potential harm.

Rheological Characterization of Environmental Slurries

The analysis of environmental slurries and complex waste streams presents another distinct operational challenge. These fluids often contain suspended particulates, fibers, and sludge. These contaminants can jam traditional narrow-gap instruments like cone-and-plate geometries. Specialized geometries are required for accurate measurement.

Vane rotors or wide-gap concentric cylinders are often the tools of choice. They allow for the accurate characterization of sludge and sediment-laden waters. They do this without creating wall-slip artifacts or particle jamming. This data is essential for designing pumping systems.

It is critical for wastewater treatment plants and dredging operations. Proper data ensures that machinery is appropriately sized. It must handle the specific flow resistance of the slurry. Understanding the rheology of these materials allows for the optimization of flocculant addition.

This improves the efficiency of dewatering processes. It also minimizes the environmental footprint of waste management operations.

Industrial Applications: Viscosity of Fertilizers and Industrial Coatings

The industrial sector demands robust and versatile rheological testing. This testing ensures the performance of bulk materials that fuel the global economy. Fertilizers, particularly liquid suspensions and foliar feeds, present unique challenges. They must remain homogenous during extended storage periods and subsequent application.

If the viscosity is too low, vital nutrients may precipitate out of the solution. This settling follows Stokes' Law. It leads to hard-packing at the bottom of the container. This results in uneven application in the field.

Conversely, excessive thickness can clog precision spraying equipment. This causes downtime and erratic coverage. Rheology helps agrochemical formulators optimize suspending agents. Rheology modifiers are used to achieve a stable shelf life. They ensure the fluid shears sufficiently to pass through spray nozzles. The fluid must also wet the leaf surface effectively.

Industrial Coatings and Paints

Industrial coatings and paints represent another domain where rheology dictates performance. It controls application performance and final finish quality. A high-performance coating must exhibit a complex rheological profile. It needs high viscosity at low shear rates.

This prevents sagging or dripping after application on a vertical surface. However, it requires low viscosity under high shear. High shear occurs during brushing, rolling, or spraying. This low viscosity ensures smooth, easy application.

This time-dependent recovery of structure after shearing is known as thixotropy. Laboratories meticulously test for thixotropic loops and structure recovery rates. These tests predict how well a paint will level out. The goal is to remove brush marks before drying.

A coating with poor leveling will show striations and texture. One with poor sag resistance will result in unsightly drips and curtains.

The Paint Application Rheology Cycle:

- Storage (Ultra-Low Shear): High viscosity required to prevent pigment settling.

- Pumping/Mixing (Medium Shear): Shear thinning required to move fluid through pipes.

- Application/Spraying (High Shear): Low viscosity required for atomization and smooth transfer.

- Leveling (Low Shear): Controlled viscosity recovery to allow smoothing without dripping.

Polymerization and Curing

The synthesis of polymers, resins, and adhesives involves monitoring molecular weight changes. These changes correlate directly with viscosity evolution. As polymerization proceeds, the resistance to flow increases exponentially. This marks the transition from monomer to polymer.

Lab operations monitoring these reactions often use torque-based process viscometers. They determine the precise endpoint of a reaction. Stopping the reaction too early results in a soft, tacky product. This unusable product has insufficient molecular weight.

Over-processing can lead to brittle materials or cross-linked gels. It can even cause catastrophic equipment damage due to motor overload. By leveraging precise rheological data, chemical engineers can fine-tune reaction kinetics. They can optimize catalyst efficiency.

They ensure that the final polymer meets rigorous mechanical specifications. These specifications are required for its end use.

Elevating Lab Operations through Viscosity and Rheology

The precise measurement of viscosity and rheology is fundamental to the success of modern lab operations. Whether characterizing injectable drugs for patient safety, ensuring sensory appeal in food quality control, or monitoring environmental slurries, accurate data is key. The ability to quantify fluid behavior under stress drives innovation. It also drives compliance and efficiency.

As industries face increasing demands for reproducibility, traceability, and cost-effectiveness, advanced tools are essential. The adoption of inline rheology monitoring is becoming imperative. Sealed systems for hazardous fluids are also becoming standard. By prioritizing these analytical techniques, laboratories enhance their capabilities.

Integrating these methods into the core of laboratory workflows ensures robust data. It keeps operations safe and compliant. The results become truly indicative of real-world performance. The integration of rigorous flow characterization protocols bridges a critical gap.

It connects theoretical formulation with practical application. This ensures that the fluids powering our world flow exactly as intended.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.