The application of rheological testing in forensic material studies provides objective, quantitative data regarding the flow and deformation behavior of physical evidence found at crime scenes. By measuring parameters such as viscosity, viscoelasticity, and yield stress, forensic scientists can characterize complex materials ranging from coagulating blood to degrading synthetic polymers. These measurements allow investigators to move beyond subjective visual assessments and establish empirical timelines for biological processes. Laboratory professionals utilize rotational and oscillatory rheometers to simulate environmental conditions and observe how material properties change over time.

Principles of rheological testing in forensic material studies

Rheological testing measures how materials respond to applied forces, distinguishing between elastic solids, viscous liquids, and viscoelastic materials common in forensic contexts. The primary objective in a forensic setting is to generate a material "fingerprint" that can link a sample to a specific source or point in time. Understanding the balance between the storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G'') is essential for interpreting evidence stability.

Non-Newtonian behavior is a critical concept when analyzing forensic fluids. Many biological substances, such as blood and synovial fluid, exhibit shear-thinning properties where viscosity decreases under strain. Rheometers capture these non-linear responses to model how fluids behave during a criminal event, such as high-velocity impact spatter.

The determination of yield stress offers insight into the static properties of substances found at a scene. Yield stress defines the minimum stress required to initiate flow, which helps determine if a substance, such as a drying adhesive or paint smear, has been disturbed. Accurate yield stress measurement relies on controlled stress ramps to identify the exact breakdown of the structural network.

Thixotropy, the time-dependent recovery of viscosity, is another vital parameter in forensic material studies. This property is particularly relevant when analyzing paints, inks, or biological sludges that structure themselves at rest. By characterizing thixotropic loops, analysts can estimate how long a material has been undisturbed on a surface.

Laboratory professionals must select the appropriate geometry for the sample type, such as cone-and-plate for low-volume biofluids or parallel plates for gels. The choice of geometry directly influences the shear rate distribution and the accuracy of the resulting data. Calibration with standard oils ensures that instrument compliance does not skew the measurement of trace evidence.

Estimating post-mortem intervals using biological fluid rheology

Rheological testing of biological fluids provides a biophysical marker to support the estimation of the post-mortem interval (PMI). Blood, vitreous humor, and synovial fluid undergo distinct rheological transitions due to temperature drops and enzymatic activity after death. Oscillatory shear tests measure these transitions, tracking the evolution of viscoelastic moduli alongside standard chemical analysis.

Whole blood exhibits complex rheological changes immediately following extravasation and cessation of circulation. As coagulation cascades initiate, the fluid transitions from a liquid sol to a viscoelastic gel. Rheometry characterizes the clotting status and the stiffness of the clot (G'), which helps differentiate between fresh, coagulating, and dried blood.

Forensic research indicates that the viscosity of synovial fluid changes predictably as hyaluronic acid degrades post-mortem. Frequency sweeps on synovial fluid reveal reductions in overall viscoelasticity and the crossover frequency of G' and G''. This degradation profile serves as a supplementary physical indicator of PMI, complementing traditional biochemical markers like potassium concentration.

The influence of temperature on biological rheology follows the Arrhenius relationship, requiring precise thermal control during analysis. Forensic laboratories typically perform temperature sweeps to model the environmental conditions the body was exposed to. This modeling helps correct rheological data for variables such as outdoor exposure or refrigeration.

Vitreous humor, the fluid within the eye, maintains a relatively stable environment but undergoes liquefaction linked to collagen network breakdown. Low-shear viscosity measurements of vitreous humor can quantify this physical loss of structure. This data is often cross-referenced with chemical analysis to narrow the time of death window.

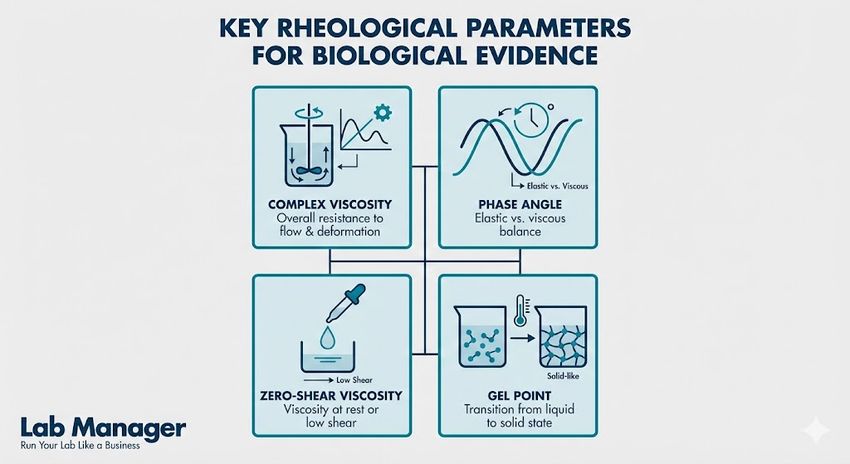

Accurate characterization of biological evidence relies on understanding how samples respond to stress and deformation.

GEMINI (2026)

Key rheological parameters for biological evidence include:

- Complex Viscosity (eta): Indicates the total resistance to flow under oscillating stress.

- Phase Angle (delta): Quantifies the degree of viscoelasticity (0° for solids, 90° for liquids).

- Zero-Shear Viscosity (eta0): Reflects the material's structure at rest, useful for detecting sedimentation.

- Gel Point: The moment where G' equals G'', signaling a phase transition in clotting blood or curing resins.

Analyzing polymeric trace evidence and adhesives with rheology

Rheological profiling distinguishes chemically similar polymeric materials by identifying differences in molecular weight distribution, branching, and filler content. Trace evidence such as pressure-sensitive adhesives (tapes), automotive paints, and cosmetic residues are frequently subjected to dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) or rheological shear testing. These physical profiles can differentiate between batches of manufacturing or link a specific roll of tape to a crime scene.

Pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSAs) rely on a specific balance of tack and shear holding power, which relates directly to rheological windows defined by the Dahlquist criterion. Frequency sweeps on PSA samples reveal the bonding efficiency at different time scales. A mismatch in the rheological fingerprint between a reference sample and evidence suggests they originated from different sources.

Curing profiles of epoxies and industrial glues recovered from explosive devices or makeshift weapons provide temporal evidence. By measuring the chemorheology—the change in flow properties during a chemical reaction—analysts can estimate how recently an adhesive was mixed and applied. This requires simulating the curing temperature profile within the rheometer's environmental chamber.

Automotive paints exhibit unique viscoelastic signatures above their glass transition temperature (Tg). While infrared spectroscopy identifies chemical composition, rheological testing characterizes the mechanical durability and thermal history of the paint film. Small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) tests are non-destructive, preserving the sample for further elemental analysis.

Cosmetic residues, such as lipsticks or foundations transferred during physical alterations, possess complex structured fluid properties. These materials contain waxes and oils that dictate their melting point and spreadability. Temperature ramps can generate a "melting profile" that serves as a comparative identification tool between suspect and victim.

Material Type | Primary Rheological Test | Forensic Application |

|---|---|---|

Blood | Time-sweep oscillation | Coagulation status / Event sequencing |

Adhesives (Tape) | Frequency sweep | Source comparison / Batch identification |

Paints | Temperature ramp / DMA | Vehicle identification / Aging analysis |

Inks/Gels | Thixotropic loop | Aging of documents / Deposition timing |

Soil/Mud | Yield stress measurement | Geolocation / Transfer analysis |

Standardizing rheological testing protocols for forensic labs

Establishing standardized protocols for rheological testing is essential to ensure that data is admissible in court and reproducible across different laboratories. Unlike chemical analysis, where spectral libraries are vast, rheological databases for forensic materials are still being developed. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) provides general guidelines for rheological measurements (e.g., ASTM D4287 for paints), but forensic-specific adaptations are necessary.

Sample handling history significantly affects rheological data, particularly for biological and thixotropic materials. Protocols must define the exact shear history, thermal equilibration time, and loading technique to prevent operator-induced variability. For example, "pre-shearing" a sample is often required to erase the mechanical memory of the loading process.

Instrument calibration and verification are critical for maintaining the chain of custody for scientific data. Regular checks with certified reference materials (Newtonian oils) ensure that the gap setting, torque sensitivity, and temperature control are within specified tolerances. Discrepancies in gap height as small as microns can introduce significant errors in viscosity calculations.

Reporting requirements for forensic rheology must include all experimental conditions, not just the final values. This includes the geometry used (e.g., 40mm parallel plate), the gap size, the temperature, and the applied stress or strain range. Providing raw data curves alongside calculated parameters allows peer reviewers to assess the quality of the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

Inter-laboratory studies are increasingly vital for validating rheological methods in forensic science. Collaborative exercises help quantify the uncertainty of measurement associated with complex heterogeneous samples like mud or stomach contents. Reducing measurement uncertainty strengthens the evidentiary weight of rheological findings in legal proceedings.

Optimizing sample volume and loading for forensic accuracy

Consistent sample volume and loading techniques are paramount when performing rheological testing in forensic material studies to avoid experimental artifacts. Underfilling or overfilling the gap in a rotational rheometer changes the effective shear rate and introduces edge failure effects. For forensic samples, which are often limited in quantity, laboratory professionals must utilize solvent traps to prevent evaporation during long tests. Standard operating procedures typically dictate that excess sample must be trimmed flush with the geometry edge to maintain the assumption of ideal flow. The normal force applied during loading must also be monitored and allowed to relax to zero before testing begins. Any residual stress from the loading phase can manifest as false yield points or skewed low-frequency moduli.

Advancing forensic material studies with rheological testing

Rheological testing in forensic material studies serves as a powerful, quantitative tool for characterizing the physical states of biological and synthetic evidence. By measuring fundamental properties such as viscosity, viscoelasticity, and yield stress, forensic laboratories can extract time-dependent data that chemical analysis alone cannot provide. These insights are critical for characterizing physical degradation, comparing trace polymers, and reconstructing timeline events involving fluids. As the field advances, the integration of standardized rheological protocols will further enhance the reliability and courtroom admissibility of this complex data.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.