Mass spectrometry provides laboratory professionals with unparalleled sensitivity and specificity for determining the elemental and molecular composition of solid surfaces. Integrating mass spectrometry into materials surface analysis workflows allows for the detection of trace contaminants, the mapping of chemical distributions, and the precise characterization of thin films at the nanometer scale. This analytical capability is essential for quality control and failure analysis in semiconductor manufacturing, polymer engineering, and advanced metallurgy. Modern instrumentation enables the differentiation of isotopes and molecular fragments, providing structural elucidation that other surface techniques like XPS or AES may miss.

Principles of surface ionization and detection mechanisms

Mass spectrometry relies on the desorption and ionization of surface atoms and molecules to generate charged particles for analysis. In materials surface analysis, the primary mechanism involves bombarding the sample with a primary ion beam, laser, or plasma to eject secondary ions from the uppermost monolayers. These ions are then accelerated into a mass analyzer, such as a Time-of-Flight (ToF) or quadrupole system, which separates them based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z).

Efficiency in ionization is critical for achieving low detection limits in surface characterization. The ionization yield—the fraction of sputtered atoms that become ionized—varies significantly depending on the matrix and the element being analyzed. Techniques to enhance ionization, such as using reactive primary ion beams (e.g., Cs+ or O2+), are standard practice to increase sensitivity for electronegative or electropositive elements, respectively.

Depth of information is a defining characteristic of surface mass spectrometry. Most techniques, particularly Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS), draw information from the top 1–2 monolayers (~0.5–2 nm) of the material. This extreme surface sensitivity allows researchers to distinguish between surface contamination and bulk composition differences.

Key Ionization Sources

- Liquid Metal Ion Guns (LMIG): Utilize gallium LMIGs or bismuth/gold cluster sources for high spatial resolution imaging and enhanced molecular ion yields.

- Gas Cluster Ion Beams (GCIB): Employ argon clusters to minimize surface damage during organic depth profiling, preserving molecular structure.

- Plasma Sources: Used in Glow Discharge Mass Spectrometry (GDMS) for direct solid analysis of bulk conductive and non-conductive materials.

Secondary ion mass spectrometry capabilities for high-sensitivity analysis

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) is among the most sensitive techniques available for materials surface analysis, capable of detecting elements in the parts-per-billion (ppb) range. Detection limits depend strongly on the element and matrix. The technique operates in two distinct modes: static SIMS for molecular surface characterization and dynamic SIMS for in-depth elemental profiling. Selecting the appropriate mode depends on whether the analytical goal is preserving molecular integrity or quantifying elemental concentration as a function of depth.

Static SIMS utilizes a low primary ion dose (typically <10^13 ions/cm²) to analyze the top monolayer without significant surface damage. This mode is ideal for identifying organic contaminants, polymer additives, and molecular orientation on surfaces. Time-of-Flight (ToF) analyzers are commonly paired with static SIMS to capture a full mass spectrum in parallel, ensuring high transmission efficiency.

Dynamic SIMS employs high ion currents to sputter away material continuously, allowing for depth profiling from a few nanometers to several micrometers. This method is the industry standard for measuring dopant profiles in semiconductors and characterizing multilayer thin films. Quantification in dynamic SIMS requires the use of relative sensitivity factors (RSFs) derived from ion-implanted standards to correct for matrix effects.

Table 1: Comparison of Static vs. Dynamic SIMS

Feature | Static SIMS | Dynamic SIMS |

|---|---|---|

Primary Dose | Low (<10^13 ions/cm²) | High (>10^13 ions/cm²) |

Information Depth | Top 1–2 monolayers (~0.5–2 nm) | Bulk / Depth profiling (>1 µm) |

Primary Application | Molecular identification, organic mapping | Elemental depth profiling, trace analysis |

Typical Analyzer | Time-of-Flight (ToF) | Magnetic Sector or Quadrupole |

Laser ablation and desorption techniques for spatial mapping

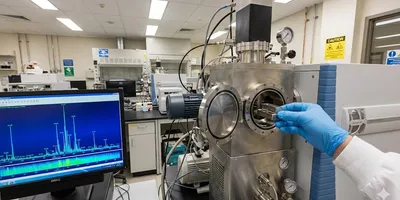

Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) offers a robust alternative for materials surface analysis when spatially resolved elemental analysis is required without high vacuum constraints on the sample environment. A high-energy laser pulse ablates a small portion of the sample surface, generating an aerosol that is transported to an ICP-MS for ionization and detection. This technique is particularly effective for geological materials, ceramics, and metallic alloys where minimal sample preparation is desired.

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) extends mass spectrometry utility to fragile organic coatings and biomaterials. By embedding the analyte in a crystalline matrix, MALDI facilitates soft ionization that preserves the molecular weight of large polymers and biomolecules. This capability is crucial for analyzing surface functionalization on medical devices and biosensors.

Lateral resolution in laser-based techniques is generally limited by the laser spot size, typically in the range of 1–100 micrometers depending on the focusing optics. While this is lower resolution than the nanometer-scale capabilities of SIMS, the speed of analysis and the ability to operate on rougher surfaces provide significant operational advantages. Recent advancements in femtosecond lasers are further pushing these limits, enabling clearer ablation craters with reduced thermal damage to surrounding material.

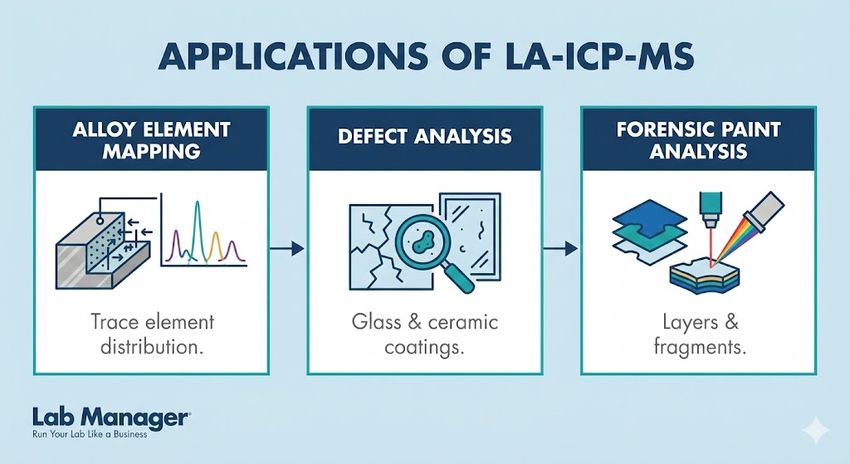

Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) is a versatile tool for solid sample analysis. Whether you are mapping trace elements in metal alloys, identifying defects in ceramic coatings, or performing forensic analysis on paint layers, this technique offers the high sensitivity and spatial resolution required for critical material insights.

GEMINI (2026)

Applications of LA-ICP-MS include:

- Mapping trace element distribution in alloy cross-sections.

- Defect analysis in glass and ceramic coatings.

- Forensic analysis of paint layers and fragments.

Overcoming quantification challenges in surface mass spectrometry

Quantifying data from mass spectrometry in materials surface analysis requires rigorous calibration due to the prevalence of matrix effects. Matrix effects occur when the chemical environment of the sample surface alters the ionization probability of the analyte. This phenomenon means that signal intensity is not always directly proportional to concentration across different materials.

To mitigate these errors, laboratory professionals must use matched standards or ion-implanted reference materials. For dynamic SIMS, the Relative Sensitivity Factor (RSF) is calculated by analyzing a sample with a known dosage of the analyte element. Applying the correct RSF is essential for converting raw count rates into accurate concentration values (atoms/cm³).

Spectral interference is another significant hurdle, particularly when isobaric ions (ions with the same nominal mass) are present. High-mass-resolution analyzers, such as magnetic sector instruments or reflective ToF systems, are necessary to resolve these interferences. For example, distinguishing between 31P and 30SiH in silicon analysis requires a mass resolving power (M/ΔM) of ~4,000 or greater, achievable with modern sector instruments.

Data handling protocols typically involve:

- Mass Calibration: Ensuring the m/z scale is accurate using known peaks (e.g., hydrocarbon fragments).

- Dead Time Correction: Adjusting for detector saturation during high count rates.

- Normalization: Referencing signal intensity to a matrix ion to account for fluctuations in primary beam current.

Sample preparation best practices for materials surface analysis

Proper sample preparation is the foundational step that dictates the quality and reproducibility of mass spectrometry data in materials surface analysis. Samples must be compatible with ultra-high vacuum (UHV) environments, meaning they should be dry, non-volatile, and securely mounted. Surface contamination from handling, packaging, or atmospheric exposure can obscure the true surface composition, making clean handling protocols utilizing powder-free gloves and non-silicone tools mandatory. For insulating materials, charge buildup can distort the primary beam and secondary ion trajectories, leading to unstable signals. To counteract charging, laboratory professionals often coat samples with a conductive layer (such as gold or carbon) or utilize electron flood guns to neutralize the surface charge during analysis. Ensuring the sample is flat and smooth is also critical, as surface roughness can degrade depth resolution and introduce topographic artifacts in imaging modes.

The critical role of mass spectrometry in materials surface analysis

Mass spectrometry remains a cornerstone of materials surface analysis, offering indispensable insights into surface chemistry, layer structure, and trace contamination. By selecting the appropriate ionization method—whether SIMS for nanometer-scale resolution or LA-ICP-MS for rapid elemental mapping—laboratories can tailor their analytical strategy to specific material challenges. Success relies on a strong understanding of matrix effects, rigorous calibration using standard reference materials, and meticulous sample preparation. As materials engineering advances toward smaller scales and more complex interfaces, the role of high-sensitivity surface mass spectrometry will continue to expand.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.