Mass spectrometry serves as an essential component of analytical precision in modern laboratory workflows, enabling the identification and quantification of complex molecular structures with exceptional sensitivity. By measuring the mass-to-charge ratio of ions, mass spectrometry provides critical data that informs clinical decisions, pharmaceutical development, and environmental safety standards.

This analytical platform has evolved from a specialized physics tool into a ubiquitous system indispensable for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and high-throughput proteomics. As laboratory standards become increasingly stringent, the mastery of mass spectrometry remains a primary requirement for professionals dedicated to scientific excellence and rigorous industry outcomes.

Technical evolution of mass spectrometry analyzers

The fundamental utility of mass spectrometry lies in its ability to convert neutral molecules into gas-phase ions. The process involves three primary stages: ionization, mass analysis, and detection. In the ionization stage, techniques such as electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) have expanded the field by allowing for the analysis of large, non-volatile biomolecules without significant fragmentation.

ESI, in particular, has enabled the seamless coupling of liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry, creating the robust LC-MS platforms used today. Advanced variants, such as heated electrospray ionization (HESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), further extend the reach of the technology to molecules across a broad range of polarities, facilitating more diverse laboratory applications.

Once ionized, the particles enter the mass analyzer, which acts as the center of the system. The choice of analyzer significantly impacts resolution, mass accuracy, and the dynamic range of the data. Professionals must select analyzers based on the specific needs of their workflow, balancing speed against the required depth of molecular information.

Analyzer type | Mechanism of action | Primary laboratory use |

|---|---|---|

Quadrupole | Uses oscillating electrical fields to filter ions by mass. | Quantitative analysis, environmental testing, and routine screening. |

Time-of-flight (TOF) | Measures the time ions take to travel a fixed distance. | High-resolution discovery, accurate mass measurement, and proteomics. |

Ion trap | Captures ions in a 3D field for sequential fragmentation. | Structural elucidation, multi-stage MS/MS studies, and metabolite ID. |

Orbitrap | Ions oscillate around a central spindle; frequency determines mass. | Ultra-high resolution, complex omics research, and isotope analysis. |

The integration of these analyzers into tandem systems (MS/MS), such as the triple quadrupole (QqQ) or the quadrupole-time-of-flight (Q-TOF), allows laboratory professionals to perform "bottom-up" or "top-down" analyses. This technical depth is necessary when distinguishing between nearly identical isotopes or metabolites in a complex biological matrix, ensuring that the final data is both accurate and reproducible.

Proteomics and clinical research via LC-MS

In the realm of life sciences, mass spectrometry is a primary tool for proteomics. The characterization of the entire protein complement of a cell or tissue requires the high resolution and sensitivity provided by LC-MS systems. By coupling liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry, researchers can separate complex mixtures of peptides or proteins before they enter the mass spectrometer, significantly reducing ion suppression and increasing the depth of coverage.

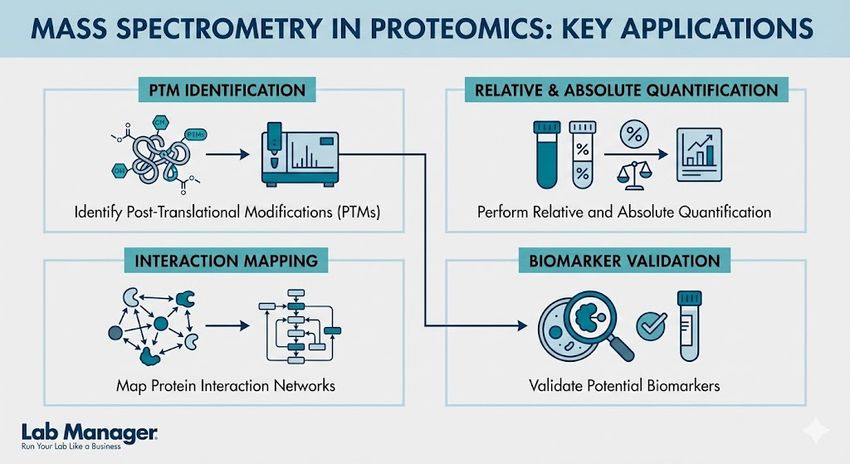

In proteomics, mass spectrometry is utilized for:

Mass spectrometry has become the gold standard in proteomics, offering unparalleled precision for modern laboratories.

GEMINI (2026)

- Identification of post-translational modifications (PTMs): Mapping phosphorylation, glycosylation, and acetylation sites that dictate protein function and signaling pathways.

- Relative and absolute quantification: Utilizing stable isotope labeling techniques like TMT or iTRAQ, as well as label-free methods, to determine protein expression levels across different biological states.

- Mapping interaction networks: Using cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) to visualize protein-protein interaction surfaces.

- Biomarker validation: Moving from discovery-based proteomics to targeted assays, such as selected reaction monitoring (SRM), for disease detection.

The precision of LC-MS is vital in clinical settings where the complexity of human plasma or tissue can overwhelm simpler analytical techniques. Unlike traditional immunoassays, which can suffer from cross-reactivity and the "hook effect," mass spectrometry offers specificity by measuring the molecular mass of the analyte itself.

This capability is critical in clinical toxicology, where the accurate identification of drug metabolites informs patient care pathways. Furthermore, the ability of mass spectrometry to handle low-abundance proteins enables the discovery of novel therapeutic targets that were previously difficult to detect, advancing the progress of personalized medicine.

Pollutant monitoring and pesticide residue analysis

The application of mass spectrometry extends beyond the clinical lab into the sectors of public health and environmental protection. Pollutant monitoring relies heavily on the sensitivity of mass spectrometry to detect trace levels of contaminants in air, water, and soil. Organic pollutants, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), require the high-precision detection capabilities of tandem mass spectrometry to meet evolving environmental regulations.

In the food industry, mass spectrometry is the primary tool for ensuring consumer safety through the detection of:

- Pesticide residue: Systematic screenings of produce and grain to ensure compliance with maximum residue limits (MRLs) established by international regulatory bodies.

- Food contamination: Rapid identification of heavy metals, mycotoxins, and illegal additives like melamine or Sudan dyes.

- Authenticity and origin testing: Using isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) to verify the geographical origin of goods like honey or wine to prevent food fraud.

Pesticide residue analysis often utilizes triple quadrupole mass spectrometry due to its quantitative performance and "selective reaction monitoring" (SRM) capabilities. The use of internal standards—often isotopically labeled analogs—allows for the correction of matrix effects, ensuring accuracy even in complex samples like oils or spices.

This high-throughput capability is necessary for regulatory bodies and commercial labs tasked with processing large sample volumes daily. By providing a molecular fingerprint, mass spectrometry helps ensure that the global food supply chain remains transparent and compliant with international trade standards.

Materials surface analysis and forensic toxicology

The versatility of mass spectrometry is demonstrated in materials science and forensics. Materials surface analysis employs techniques like secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) to characterize the top atomic layers of a solid sample. This is critical in the semiconductor and nanotechnology industries, where minute impurities can lead to device failure. SIMS provides sensitivity for surface species, allowing engineers to map the distribution of dopants and contaminants with nanometer-scale depth resolution.

In the field of toxicology, mass spectrometry is utilized for both post-mortem investigations and workplace drug testing. Forensic toxicology laboratories depend on the technique to provide results that withstand high levels of scrutiny. The ability to distinguish between illicit substances and over-the-counter medications that share similar chemical structures is a significant advantage of mass spectrometry.

Key forensic applications include:

- Seized drug analysis: Confirming the identity and purity of unknown substances using high-resolution mass spectrometry.

- Doping control in sports: Utilizing high-resolution instruments to detect performance-enhancing drugs and their metabolites at sub-nanogram levels.

- Hair analysis for chronic exposure: Providing a long-term history of substance exposure, which is useful in child custody cases or rehabilitation monitoring.

The objectivity of mass spectrometry data makes it a vital component of the judicial process. Unlike presumptive color tests or rapid screens, mass spectrometry provides a confirmatory result, offering evidence that is suitable for scientific peer review and legal cross-examination.

Solvent safety and regulatory submission compliance

Maintaining a high-functioning mass spectrometry laboratory requires more than technical expertise; it demands rigorous operational standards. Solvent safety is a priority, as the mobile phases used in LC-MS—such as acetonitrile, methanol, and additives like formic acid—are often volatile, flammable, and toxic. Laboratory professionals must implement protocols for solvent storage and waste disposal to comply with OSHA and local environmental standards.

Key safety considerations include:

- Vapor management: Using specialized safety caps with integrated filters on solvent bottles to prevent the escape of vapors and the ingress of contaminants.

- Fire prevention: Storing bulk flammable solvents in grounded, fire-rated cabinets and ensuring that LC-MS waste lines are properly sealed.

- Personal protective equipment (PPE): Ensuring the use of chemical-resistant gloves, eye protection, and lab coats when preparing mobile phases or cleaning ion sources.

Furthermore, the data generated by mass spectrometry is often a central component of a regulatory submission. Whether seeking FDA approval for a new drug or submitting environmental impact reports to the EPA, the integrity of the mass spectrometry data is under constant scrutiny. This necessitates a robust quality management system (QMS) and adherence to good laboratory practices (GLP).

To ensure a successful regulatory submission, laboratories focus on several fundamental pillars:

- Method validation: Testing to demonstrate that the method is accurate, precise, and reproducible. Parameters include assessing the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) and the impact of matrix effects.

- Data integrity and traceability: Maintaining unalterable electronic records and detailed audit trails to comply with regulations such as 21 CFR part 11.

- Instrument qualification (IQ/OQ/PQ): A documented process showing the instrument was installed correctly, operates as intended, and performs consistently over time.

- System suitability testing (SST): Daily checks using standardized mixtures to ensure that the system is performing within defined specifications.

Adhering to these standards ensures that the laboratory’s output is reliable, facilitating the movement of products from the bench to the global market.

Data interpretation and AI in mass spectrometry

As the volume of data produced by modern spectrometers grows, the bottleneck has shifted from data acquisition to data interpretation. High-resolution instruments can produce gigabytes of data per sample, necessitating advanced bioinformatics tools. Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are now being integrated into mass spectrometry workflows to automate peak picking and predict fragmentation patterns.

In the context of proteomics and metabolomics, AI-driven algorithms can:

- Predict retention times: Helping to identify unknown compounds in complex matrices by comparing chromatographic behavior.

- Enhance library searching: Improving match scores between experimental spectra and reference databases.

- Identify novel metabolites: Detecting previously uncharacterized molecules in biological samples that might be indicators of disease.

For the laboratory professional, staying current with these digital transformations is as important as mastering the hardware. The ability to interpret complex MS/MS data and understand software limitations is a hallmark of a proficient practitioner in the field.

Future horizons: Ambient ionization and portability

The future of mass spectrometry involves bringing the lab to the sample. Ambient ionization techniques, such as desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) and direct analysis in real time (DART), allow for the analysis of samples in their native state with minimal preparation. This has implications for rapid screening in airports, hospitals, or on the factory floor for quality control.

Furthermore, the miniaturization of mass analyzers is leading to the development of portable units. These systems are beginning to be used for:

- On-site pollutant monitoring: Detecting chemical spills or air quality issues in real-time.

- Point-of-care (POC) testing: Providing immediate results for medical crises in emergency rooms.

- Agricultural field testing: Checking for pesticide residue on crops before they are harvested.

While these portable systems currently lack the ultra-high resolution of laboratory-based systems, their ability to provide immediate answers is changing how industries approach molecular analysis.

Mass spectrometry in laboratory science

In conclusion, mass spectrometry remains a transformative force in molecular analysis, providing the clarity required to solve complex scientific challenges. From the mapping of the human proteome via LC-MS to the detection of pesticide residue and pollutant monitoring, its applications are essential to modern society.

Laboratory professionals who prioritize technical proficiency, solvent safety, and rigorous data management for regulatory submission are best positioned to leverage this technology for scientific outcomes. As mass spectrometry continues to evolve toward higher resolution and greater portability, it will remain a primary analytical tool for unlocking the molecular world.

This article was created with the assistance of generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.