Adoption of X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for soil nutrient and mineral analysis transforms how agricultural and environmental laboratories process samples. This technique delivers rapid, simultaneous multi-element quantification. It significantly reduces turnaround times compared to conventional wet chemistry. Laboratory professionals utilize XRF to determine total elemental composition. This data aids in robust soil characterization and fertility assessments. The integration of high-throughput XRF instrumentation allows for the efficient screening of vast sample numbers. This capacity supports both precision agriculture and environmental monitoring initiatives.

Principles of XRF for soil nutrient and mineral analysis

X-ray fluorescence operates on atomic physics principles to identify and quantify elements within a soil matrix. High-energy primary X-rays generated by an X-ray tube strike the soil sample, dislodging electrons from the inner orbital shells of the atoms present. Electrons from outer shells immediately transition to fill these vacancies, releasing excess energy in the form of fluorescent X-rays. This emitted radiation possesses a characteristic energy profile specific to each element, allowing the detector to identify which elements are present and in what concentrations.

For soil analysis, two primary configurations exist: Energy Dispersive XRF (EDXRF) and Wavelength Dispersive XRF (WDXRF). EDXRF systems provide simultaneous acquisition of the entire spectrum, making them highly efficient for rapid screening and field applications. WDXRF systems physically separate X-rays based on wavelength using diffraction crystals before detection. This physical separation offers superior spectral resolution, effectively eliminating many overlapping peaks common in complex soil matrices. WDXRF often delivers improved precision and sensitivity for light elements under optimized conditions, making it the preferred choice for reference laboratories requiring rigorous data quality. Understanding these physical configurations ensures laboratories select the right instrument for their specific sensitivity needs.

Optimizing sample preparation for accurate XRF soil analysis

Achieving accurate XRF for soil nutrient and mineral analysis relies heavily on physical sample preparation. Unlike wet chemistry, where acids dissolve the matrix, XRF analyzes the solid sample directly. Consequently, physical inconsistencies such as particle size, mineralogy, and moisture content directly influence the analytical signal. Moisture acts as a significant interference, absorbing X-rays and diluting the elemental concentration. Laboratories must dry samples thoroughly, typically at 105°C, to ensure stable measurements.

Particle size effects represent another critical variable. Large particles scatter X-rays differently than fine powder, leading to poor reproducibility. Laboratory protocols usually require grinding soil to a fine powder, often passing through a 200-mesh (75 µm) sieve. This homogenization ensures the sample surface presented to the analyzer accurately represents the bulk material.

Two main preparation methods dominate laboratory workflows:

- Pressed pellets: Technicians mix the ground soil with a binding agent (such as wax or cellulose) and compress it under high pressure (typically 15–30 tons) into a solid disc. This method is cost-effective and provides excellent sensitivity for trace elements and heavy metals.

- Fusion beads: The analyst mixes the soil with a lithium borate flux and melts the mixture at high temperatures (>1000°C) in a platinum crucible. The resulting glass bead creates a perfectly homogeneous representation of the sample, eliminating particle size and mineralogical effects completely. This method serves as the gold standard for measuring major oxides and macronutrients with high precision.

Ultimately, meticulous preparation protocols are essential to eliminate physical interference and guarantee high-quality analytical results.

Comparing XRF against wet chemistry for soil nutrient analysis

Integrating XRF for soil nutrient and mineral analysis requires understanding the distinction between total elemental composition and bioavailable nutrients. Traditional agricultural testing relies on extraction methods, such as Mehlich-3 or DTPA. These methods use chemical solutions to mimic plant root uptake. They measure only the "available" fraction of nutrients. In contrast, XRF measures the total concentration of an element present in the soil. This measurement occurs regardless of the element's chemical form or availability to plants.

This distinction presents both a challenge and an opportunity for laboratories. XRF does not directly replace extraction methods for standard fertilizer recommendations. However, it offers complementary data that extraction alone cannot provide. Total nutrient stocks indicate the long-term weathering potential and mineral reserve of the soil. Furthermore, many laboratories develop regression models. These models correlate total XRF data with extractable nutrient levels for specific soil types. This allows for rapid screening using XRF, followed by confirming critical samples with traditional extraction.

Operational efficiency favors XRF significantly. Wet chemistry requires hazardous reagents and generates chemical waste. It also involves multiple manual steps including digestion, filtration, and dilution. XRF eliminates the need for strong acids like hydrofluoric or nitric acid, reducing safety risks and disposal costs. A single XRF instrument can run unattended with an autosampler, analyzing hundreds of samples per day without continuous operator intervention. This high-throughput capability makes it indispensable for large-scale soil mapping projects and environmental baseline studies. By balancing total elemental data with traditional extraction, laboratories can enhance their service offerings while improving operational safety and speed.

Applications of XRF in nutrient profiling and contaminant screening

XRF instruments excel at quantifying a broad spectrum of elements essential for soil health and safety. The technique simultaneously detects macronutrients, micronutrients, and potential heavy metal contaminants in a single analysis run. This versatility streamlines laboratory operations by consolidating multiple testing requirements into one workflow.

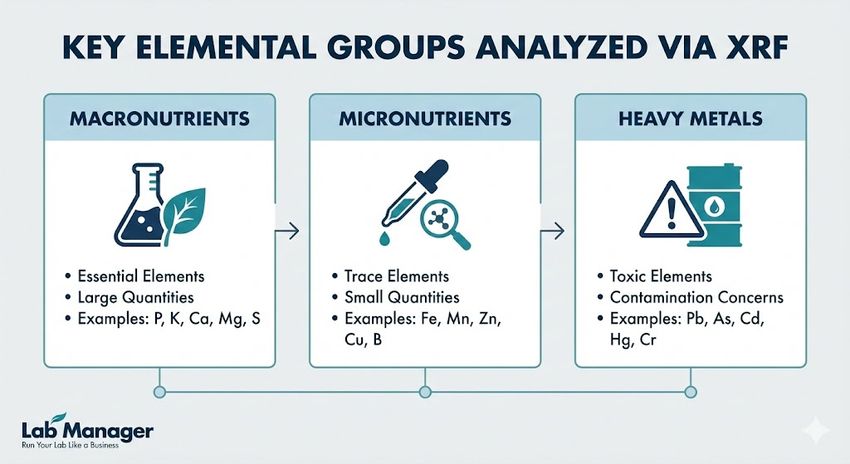

This infographic outlines the key elemental groups analyzed using X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF): macronutrients, micronutrients, and heavy metals, including examples of elements within each category.

GEMINI (2026)

Key elemental groups analyzed via XRF include:

- Macronutrients: Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K), Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), and Sulfur (S). XRF provides rapid total values for these critical fertility indicators.

- Micronutrients: Iron (Fe), Manganese (Mn), Zinc (Zn), Copper (Cu), and Molybdenum (Mo). Accurate quantification of these trace elements aids in diagnosing deficiencies affecting crop yield.

- Heavy metals: Lead (Pb), Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr), and Mercury (Hg). XRF serves as a primary screening tool for environmental compliance, detecting contamination hotspots rapidly.

Regulatory bodies and standards organizations acknowledge the utility of XRF for environmental monitoring and soil quality assessment. Method 6200, established by the US EPA, outlines the protocol for field portable XRF spectrometry. For fixed laboratory settings, ISO 18227 provides the standard guidance for determining elemental composition in soil via XRF. While Method 6200 focuses on screening, the underlying principles of rigorous calibration against standard reference materials (SRMs) apply universally. Laboratories must validate their XRF methods using certified soil standards (such as those from NIST) to ensure the accuracy of the data reported to clients. This comprehensive profiling capability allows a single instrument to serve dual roles in both agricultural fertility testing and environmental safety compliance.

Limitations of XRF for detecting light elements in soil

While XRF for soil nutrient and mineral analysis offers extensive capabilities, physics dictates specific limitations regarding light elements. Elements with low atomic numbers, specifically those lighter than sodium (atomic number 11), emit fluorescence X-rays with very low energy. These low-energy photons are easily absorbed by air, the instrument window, or the sample matrix itself. Consequently, XRF cannot detect nitrogen, a primary plant macronutrient, nor can it detect carbon, boron, or lithium effectively in standard air-path systems. Even with vacuum or helium-purge atmospheres and specialized thin-window detectors, sensitivity for these light elements remains poor compared to heavier elements. Laboratories must therefore continue to rely on combustion analysis (for carbon and nitrogen) or ICP-OES (for boron) to complete the nutrient profile. Understanding this limitation ensures laboratories apply XRF where it is most effective while maintaining alternative workflows for non-detectable elements. Acknowledging these physical limits allows laboratories to integrate XRF effectively alongside complementary techniques for complete soil characterization.

Conclusion on utilizing XRF for soil nutrient and mineral analysis

The implementation of XRF for soil nutrient and mineral analysis empowers laboratories to deliver faster, more comprehensive data to agricultural and environmental stakeholders. This technology provides simultaneous analysis of macronutrients, micronutrients, and contaminants without hazardous chemicals. Consequently, it optimizes operational efficiency and sustainability. As detector technology advances and calibration models become more robust, XRF continues to solidify its position as a cornerstone of modern soil testing strategies.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.