Viscosity testing in food quality control serves as a definitive metric for ensuring batch-to-batch consistency, optimizing processing efficiency, and maintaining consumer acceptance. Laboratory professionals rely on precise viscosity measurements to predict how liquid and semi-solid foods will behave during pumping, mixing, packaging, and consumption. This physical property directly correlates with texture, mouthfeel, and stability. It acts as a critical control point in modern food manufacturing. By establishing rigorous testing protocols, manufacturers can detect deviations early and prevent costly production failures.

Why is viscosity testing critical for food quality control?

Viscosity directly influences the sensory attributes and mechanical processing of food products. It determines whether a sauce flows correctly or a yogurt maintains its structure. Consistent viscosity ensures that products meet consumer expectations for texture and mouthfeel every time they are purchased. For automated filling lines, maintaining a specific viscosity range prevents nozzle clogging, overfilling, or underfilling of packaging containers.

As discussed in the Journal of Texture Studies article "Viscosity of liquid and semisolid materials: Establishing correlations between instrumental analyses and sensory characteristics," texture and mouthfeel are primary drivers of consumer preference in liquid and semi-solid foods. A product that is too thin may be perceived as watered-down or low quality. Conversely, a product that is excessively thick can be difficult to dispense or consume. The study confirms that viscosity testing provides the quantitative data necessary to formulate products that hit the exact sensory targets required for market success. This objective measurement replaces subjective sensory evaluation. It allows for tighter quality assurance limits.

Research in the Journal of Food Engineering study "Rheological properties of fluid fruit and vegetable puree products: Compilation of literature data" demonstrates that processing efficiency relies heavily on predictable flow behavior during manufacturing. Pumps, heat exchangers, and mixers are engineered to operate within specific viscosity profiles. If a food product deviates from these parameters, it can cause equipment strain, uneven heat transfer, or inefficient mixing. Regular monitoring allows operators to adjust process variables, such as temperature or shear rate, to maintain optimal flow characteristics.

Adhering to defined viscosity standards reduces waste and improves yield. Batch variations often result from inconsistencies in raw materials like hydrocolloids or starches. These variations can drastically alter the final product's thickness. By testing incoming ingredients and in-process samples, manufacturers can adjust formulations in real-time. This proactive approach minimizes the need for reworking or discarding off-spec batches.

Optimizing rheological properties is essential for ensuring product quality and process efficiency

GEMINI (2026)

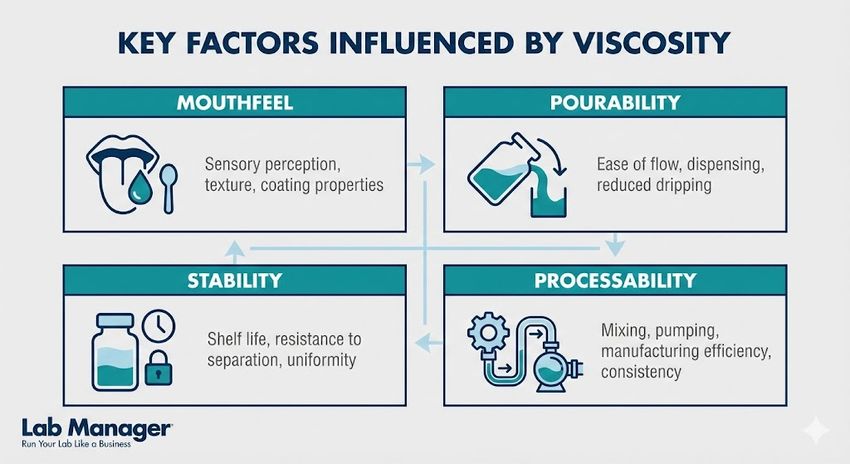

Key factors influenced by viscosity:

- Mouthfeel: Creaminess, thickness, and coating ability.

- Pourability: Ease of dispensing from bottles or tubes.

- Stability: Resistance to separation or sedimentation over time.

- Processability: Pumpability and flow through heat exchangers.

How do non-Newtonian behaviors affect food viscosity testing?

Most food products exhibit non-Newtonian behavior. This means their viscosity changes depending on the amount of shear stress applied during processing or consumption. Understanding these complex rheological profiles is essential for selecting the correct testing parameters. It is also vital for interpreting quality control data accurately. A single-point viscosity measurement is often insufficient for non-Newtonian fluids. It fails to capture the material's behavior under different flow conditions.

Shear-thinning (pseudoplastic) behavior is the most common rheological characteristic in food products like ketchup, mayonnaise, and salad dressings. These materials decrease in viscosity as shear rate increases. This allows them to flow easily when squeezed from a bottle but remain thick on the plate. Testing these products requires multipoint measurements at varying speeds to construct a flow curve. Quality control protocols must specify the exact shear rate to ensure data comparability between batches.

Shear-thickening (dilatant) fluids, while rarer in food, increase in viscosity under stress. Cornstarch suspensions are a classic example of this behavior, where rapid mixing causes the material to solidify. Though less common in finished products, shear-thickening can occur in specific high-solids processing streams. Identifying this behavior prevents equipment damage during high-speed pumping or mixing operations.

The Journal of Food Engineering article "Modelling the time-dependent rheological behavior of semisolid foodstuffs" explains that thixotropy refers to a time-dependent decrease in viscosity under constant shear. Yogurts and gels often display thixotropic properties. They break down structurally when stirred and rebuild structure when left at rest. Accurate analysis requires measuring not just the viscosity at a specific speed, but also the rate of structural recovery. This data is vital for predicting product shelf stability and preventing separation during storage.

The International Journal of Food Properties review "Yield Stress in Foods: Measurements and Applications" highlights that yield stress is the minimum force required to initiate flow in a stationary fluid. Products like ketchup or heavy sauces behave like solids until a specific yield stress is exceeded. Determining the yield point is crucial for designing packaging that allows consumers to dispense the product without excessive effort. Instruments must be capable of low-speed, high-torque measurements to accurately identify this value.

Common fluid behaviors in food:

- Newtonian: Water, oil, clear juices (viscosity is constant regardless of shear).

- Pseudoplastic: Purees, sauces, dairy emulsions (viscosity drops with shear).

- Thixotropic: Gelatinous products, set yogurts (structure breaks down over time).

- Yield Stress: Ketchup, frosting (requires force to start flowing).

Which instruments are best suited for food viscosity testing?

Selecting the appropriate viscometer depends heavily on the specific rheological properties of the food matrix. It also depends on the required precision of the quality control process. Laboratory professionals must match the instrument's capabilities—such as shear rate range, temperature control, and geometry—to the product's behavior. Using the wrong instrument type can lead to erroneous data that fails to predict real-world performance.

Rotational viscometers are the industry standard for testing non-Newtonian food products. These instruments measure the torque required to rotate a spindle immersed in the sample at a set speed. They are versatile, allowing users to alter shear rates by changing spindles or rotational speeds. Rotational viscometers are ideal for generating flow curves for sauces, dressings, and dairy products.

Capillary viscometers are primarily used for Newtonian fluids like beverages, oils, and clear broths. They measure the time it takes for a fixed volume of liquid to flow through a precision capillary tube under gravity. While highly accurate for simple fluids, they are generally unsuitable for complex, multiphase food systems. Their use is often limited to raw material testing or specific clear liquid applications.

Recent comparisons in the journal Foods, such as "Measuring Viscosity and Consistency in Thickened Liquids for Dysphagia," evaluate the correlation between different methods. The study highlights that while simple empirical tools like consistometers are useful for screening, rotational rheometers provide the necessary dynamic flow properties for critical applications. Understanding these correlations helps professionals choose between rapid floor tests and detailed laboratory analysis.

Rheometers provide the most comprehensive characterization of food structure and flow. Unlike standard viscometers, rheometers can apply both rotational and oscillatory shear to measure viscoelastic properties (G' and G''). They are essential for R&D and advanced quality control of complex structures like doughs, gels, and chocolate. Rheometers help scientists understand how a product's microstructure contributes to its macroscopic texture.

Instrument selection guide:

- Rotational Viscometer: Routine QC of sauces, creams, and dressings.

- Capillary Viscometer: QC of water, clear juices, and oils.

- Texture Analyzer: Measuring consistency of solids and semi-solids (e.g., butter).

- Rheometer: Advanced analysis of viscoelasticity and structural breakdown.

How does temperature control impact viscosity testing accuracy?

Temperature control is the single most critical variable to stabilize during viscosity testing in food quality control. Viscosity is inversely and exponentially related to temperature. A fluctuation of just one degree Celsius can result in a viscosity change of 10% or more for certain food products. This renders comparison data useless. Laboratory professionals must utilize integrated temperature baths or Peltier plates to ensure the sample remains at the defined setpoint throughout the analysis. Standard operating procedures should mandate a thermal equilibration period. This allows the entire sample volume to reach the target temperature before testing begins. Ignoring thermal history can also introduce errors. For example, fats that have crystallized and then melted may behave differently than those kept permanently liquid. Reporting viscosity without an associated temperature value makes the data scientifically incomplete and operationally actionable.

What are the regulatory standards for food viscosity?

Regulatory bodies and international standards organizations provide frameworks for viscosity testing to ensure safety, quality, and fair trade in the food industry. Adherence to these standards is often required for product certification and compliance with food safety management systems. These guidelines specify testing methods, instrument calibration requirements, and acceptable tolerance limits.

The FDA and USDA enforce standards of identity that often include viscosity or consistency requirements. For products like tomato paste, ketchup, or salad dressings, specific flow characteristics define the legal classification of the food. Compliance ensures that products are labeled correctly and meet the minimum quality expectations for that category. Inspectors frequently use the Bostwick Consistometer—a standardized flow trough—to verify these consistency standards during audits. For example, 21 CFR 155.194 outlines specific consistency requirements for ketchup.

ASTM International publishes standard test methods, such as ASTM D2196, for the rheological measurement of food materials. These methods cover the use of rotational viscometers, providing a universal protocol for testing non-Newtonian materials. Following these standardized methods ensures that results are reproducible across different laboratories and supply chain partners. This harmonization is vital for supplier qualification and raw material acceptance.

ISO standards provide global guidelines for sensory analysis and instrumental correlation. ISO 13299 outlines the general methodology for establishing sensory profiles, aiding in the correlation between physical testing and consumer experience. Global food manufacturers rely on these protocols to maintain consistent quality across facilities located in different regions.

Internal standard operating procedures (SOPs) must align with these external regulations. SOPs should detail every step of the measurement process, from sample conditioning to data recording. Regular proficiency testing and equipment calibration are essential components of a compliant quality system. Documentation of these activities provides the traceability required for food safety audits.

Key regulatory considerations:

- Standards of Identity: Legal definitions of thickness for specific foods (e.g., 21 CFR 155.194 for ketchup).

- Calibration: Regular verification of instruments using certified standard fluids.

- Traceability: Documenting method parameters (spindle, speed, temperature).

- Method Validation: Proving that an internal method yields accurate, reproducible results.

Summary of viscosity testing in food quality control

Viscosity testing in food quality control provides the objective data necessary to guarantee product consistency, optimize processing, and satisfy consumer expectations. By utilizing precise instrumentation and adhering to rigorous temperature controls, laboratory professionals can accurately characterize complex rheological behaviors. A robust viscosity testing program minimizes waste, ensures regulatory compliance, and protects brand reputation through reliable product quality.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.