X-ray fluorescence (XRF) provides a robust analytical solution for detecting trace metals in food packaging, ensuring materials meet strict safety standards and regulatory requirements. Laboratory professionals rely on this technique for its speed and accuracy in identifying hazardous elements like lead, cadmium, and mercury. Importantly, it achieves this without destroying valuable samples. The integration of XRF into quality control workflows allows for high-throughput screening of polymers, paperboards, and glass containers used in the food industry.

Principles of XRF technology for food packaging analysis

XRF technology relies on the interaction between high-energy photons and the atoms within a sample to identify elemental composition.

The fundamental process involves subjecting a sample to primary X-rays. This interaction excites the atoms and causes the ejection of electrons from inner shells. Outer-shell electrons then transition to fill these vacancies, releasing energy in the form of secondary X-ray fluorescence. Each element emits a unique energy signature, enabling precise elemental identification. Detectors measure these emissions to calculate specific elemental concentrations based on the intensity of the signal.

For food packaging analysis, energy-dispersive XRF (EDXRF) is commonly employed due to its versatility and ability to analyze a wide range of elements simultaneously. This method is particularly effective for screening solid materials, such as plastic films and cardboard, as it requires minimal sample preparation compared to wet chemistry methods. Wavelength-dispersive XRF (WDXRF) offers higher resolution and sensitivity for applications requiring lower detection limits, though it typically involves more complex instrumentation.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique used to determine the elemental composition of materials.

GEMINI (2026)

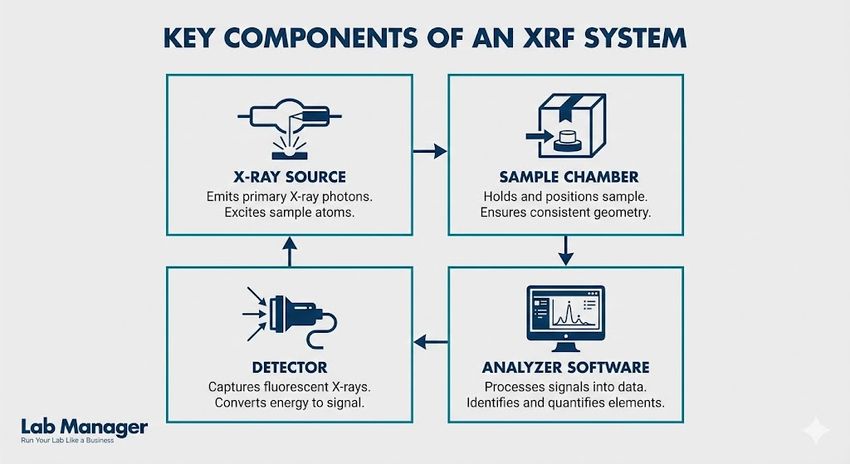

Key components of an XRF system include:

- X-ray source: Generates the primary radiation used to excite the sample.

- Sample chamber: Holds the packaging material in a controlled geometry to ensure consistent analysis.

- Detector: Measures the energy and intensity of the emitted fluorescence.

- Analyzer software: Converts the raw data into elemental concentrations and spectral displays.

The non-destructive nature of XRF serves as a significant advantage in laboratory settings. Operators can test finished packaging products or raw materials and retain the samples for further analysis or archiving. This capability supports rigorous quality assurance protocols where sample traceability remains a priority.

Detecting hazardous trace metals in packaging with XRF

Detecting toxic elements prevents the migration of harmful substances from packaging into food products.

Certain heavy metals appear in packaging materials either as intentional additives or unintentional contaminants. Manufacturers historically used lead and cadmium compounds as stabilizers or colorants in plastics, while mercury and hexavalent chromium sometimes entered the supply chain through inks, dyes, or recycled feedstocks. The primary focus of XRF analysis in this context is the detection of these four restricted metals—lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and hexavalent chromium (Cr VI)—often referred to collectively in regulatory contexts.

The source of trace metals varies by material type:

- Plastics: Stabilizers, pigments, and catalysts often contain metals like cadmium or lead.

- Paper and board: Recycled pulp may carry contaminants from previous uses, including inks and adhesives containing chromium or mercury.

- Glass: Lead is sometimes used to increase refractive index, though this is less common in standard food containers; however, external decoration and enamels may contain lead or cadmium.

- Inks and coatings: Pigments used for printing on labels and films remain a common source of heavy metal contamination.

XRF analyzers rapidly screen for these elements, providing total elemental analysis. While XRF detects total chromium rather than distinguishing between oxidation states (Cr III vs. Cr VI), a total chromium result below the regulatory threshold confirms compliance for hexavalent chromium as well. If total chromium exceeds the limit, further testing with specific methods like colorimetry or ion chromatography becomes necessary to speciate the metal.

The migration of these metals into food poses severe health risks, including neurological damage and organ failure. Consequently, the sensitivity of the analytical method must align with the low detection limits required by safety standards. Modern XRF instruments achieve limits of detection (LOD) in the parts per million (PPM) range, making them suitable for screening materials against the strict thresholds set by global health organizations.

Ensuring regulatory compliance for trace metals in packaging

Adherence to regional and international regulations mandates rigorous testing of all materials intended for direct or indirect food contact.

The regulatory landscape for food packaging creates a complex framework that laboratory professionals must navigate. In the United States, the Toxics in Packaging Clearinghouse (TPCH) model legislation serves as the benchmark for many states. This legislation prohibits the intentional introduction of lead, cadmium, mercury, and hexavalent chromium during manufacturing. Furthermore, it limits the sum of the incidental concentration levels of these four metals to less than 100 parts per million (ppm) by weight. XRF analysis allows facilities to verify compliance with TPCH requirements quickly. It often serves as the primary screening tool to ensure incidental levels remain below the 100 ppm threshold.

Similarly, the European Union enforces Directive 94/62/EC on Packaging and Packaging Waste, which imposes the same 100 ppm limit for the cumulative total of the four heavy metals when present as incidental impurities. Compliance with these statutes requires documentation that packaging materials do not exceed these trace metal thresholds. Laboratories utilize XRF to generate Certificates of Analysis (CoA) that accompany packaging lots. This document verifies that the materials are safe for use.

Regulatory bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in the EU also monitor the migration of substances. While total content analysis via XRF differs from migration testing, it acts as a critical first step. If a metal is not present in the packaging matrix, it cannot migrate into the food. Therefore, XRF screening effectively eliminates the need for migration testing on clear samples, optimizing laboratory resources.

References for regulatory limits:

- Toxics in Packaging Clearinghouse (TPCH): Updates on Model Legislation regarding the prohibition of intentional introduction and incidental limits for specific heavy metals.

- European Parliament and Council Directive 94/62/EC: Sets EU standards for heavy metals in packaging and packaging waste.

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Regulates substances for use as basic components of single and repeated use food contact surfaces under 21 CFR.

Comparing XRF analysis with ICP-MS and AAS techniques

Benchmarking XRF against alternative methods reveals its efficiency in routine screening workflows.

While Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) serve as gold standards for trace metal analysis due to their extremely low detection limits, they require destructive sample preparation. This typically involves acid digestion, where the packaging material is dissolved in strong acids under high heat and pressure. This process is time-consuming, hazardous, and generates chemical waste. In contrast, XRF requires little to no sample preparation, allowing for immediate analysis of solid samples.

The following table compares common analytical techniques used for food packaging:

Feature | X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) | ICP-MS | AAS |

|---|---|---|---|

Sample Preparation | Minimal / None | Extensive (Acid Digestion) | Extensive (Acid Digestion) |

Analysis Time | Seconds to Minutes | Hours (including prep) | Hours (including prep) |

Destructive? | No | Yes | Yes |

Detection Limits | ppm range | ppt to ppb range | ppm to ppb range |

Multi-element? | Yes (Simultaneous) | Yes (Simultaneous) | No (Sequential) |

Chemical Waste | None | High (Acids/Solvents) | High (Acids/Solvents) |

For routine compliance screening where the threshold is 100 ppm, the sensitivity of XRF is sufficient. The technique effectively identifies non-compliant samples that require further investigation. By reserving ICP-MS or AAS for borderline cases or complex matrices, laboratories optimize throughput and reduce operational costs. Furthermore, handheld XRF units allow for field testing at manufacturing sites or warehouses, a capability not matched by the laboratory-bound nature of ICP-MS instrumentation.

Managing sample thickness and homogeneity in XRF analysis

Ensuring accurate quantification requires attention to the physical properties of the packaging sample.

XRF analysis interacts with the surface and near-surface layers of a material. For the results to be representative of the entire product, the sample must be homogeneous. In the context of food packaging, multilayer films and coated cardboards present specific challenges. A thin layer of metalized film or a surface coating containing titanium dioxide can absorb X-rays or enhance the fluorescence of underlying elements, potentially skewing results. Laboratory professionals must account for "infinite thickness"—the depth at which the sample becomes opaque to the X-rays—to ensure the detector receives a consistent signal.

When analyzing thin films that do not meet infinite thickness criteria, operators typically stack multiple layers of the material until the requisite thickness is achieved. Alternatively, modern XRF software includes algorithms to correct for thickness and density variations. Calibration with matrix-matched standards further improves accuracy. Using reference materials that closely mimic the density and composition of the packaging type (e.g., polyethylene standards for plastic films) ensures that the calibration curve accurately reflects the relationship between signal intensity and elemental concentration.

The role of XRF in ensuring food packaging safety

XRF technology remains an indispensable tool for monitoring trace metals in food packaging.

The ability to rapidly detect hazardous elements like lead, mercury, cadmium, and chromium allows laboratory professionals to maintain high safety standards without the bottlenecks associated with destructive testing methods. By integrating XRF into quality control protocols, organizations ensure compliance with regulations such as TPCH and EU Directive 94/62/EC, protecting consumers from potential toxicity. As packaging supply chains become increasingly complex and globalized, the reliance on efficient, accurate, and non-destructive screening methods like XRF will continue to grow, safeguarding the integrity of the food supply.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.