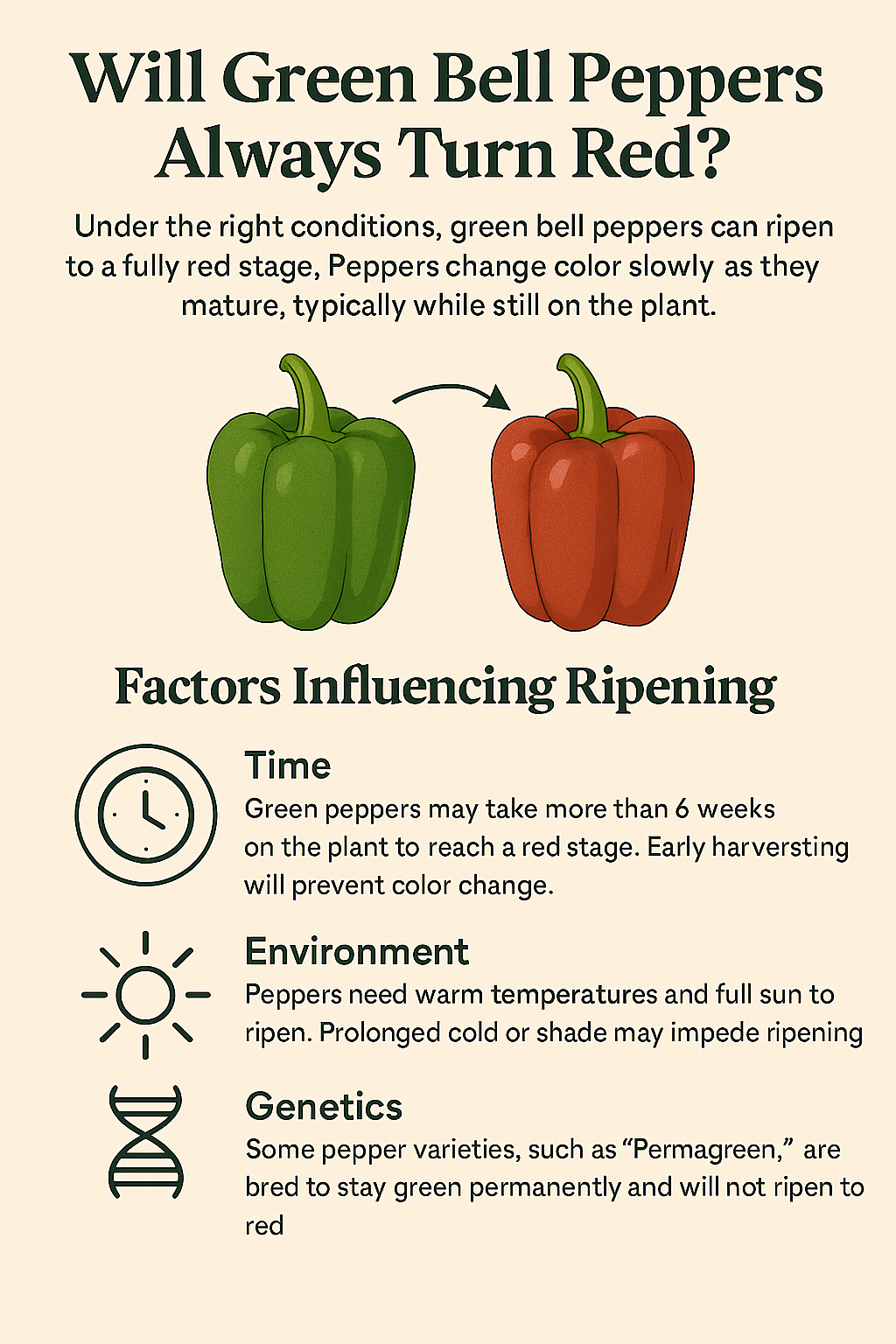

Introduction: Will Green Bell Peppers Always Turn Red?

Bell peppers (Capsicum annuum) are widely enjoyed for their vibrant colors, crisp texture, and high nutritional value. But will green bell peppers always turn red—and if so, when? The transition depends on several biological and environmental factors, and not all green peppers complete this ripening process. This color shift reflects a deeper biochemical transformation inside the fruit—a process driven by the development and differentiation of specialized cell organelles known as plastids.

A research team led by Professor Sacha Baginsky at Ruhr University Bochum (RUB) has provided the first comprehensive proteomic map of this transformation. By tracking changes at the protein level, the study reveals how chloroplasts—organelles responsible for photosynthesis—mature into chromoplasts rich in carotenoids, the pigments that give red bell peppers their color and nutritional properties.

Bell Pepper Ripening Process: How Plastids Turn Peppers Red

From Chloroplasts to Chromoplasts

The ripening of bell peppers involves the breakdown of chlorophyll and the accumulation of carotenoids, including provitamin A. These changes take place inside plastids—plant cell organelles that differentiate according to developmental and environmental cues.

- Proplastids, the precursor organelles, initially develop into chloroplasts, which are rich in chlorophyll and starch.

- As ripening progresses, chloroplasts transition into chromoplasts, which produce carotenoids and are responsible for the fruit’s red color.

This transformation is not just visual—it marks a metabolic shift from energy production via photosynthesis to antioxidant accumulation via pigment synthesis. However, whether or not a green bell pepper will turn red depends on several key factors:

Bell peppers exhibit a unique ripening strategy that utilizes repurposed photosynthetic proteins, minimal oxygen dependence, and an efficient ATP production pathway.

OpenAI (2025)

- Time on the plant: The pepper must remain attached to the plant long enough for full chromoplast development. Once harvested, non-climacteric fruits like peppers generally stop ripening.

- Environmental conditions: Sunlight, temperature, and plant health can influence the efficiency and timing of chloroplast-to-chromoplast conversion.

- Genetic variety: Some bell pepper cultivars are bred to mature into yellow or orange, not red, even when fully ripe.

If green peppers are picked too early, the transformation from chloroplasts to chromoplasts often halts, meaning the pepper will retain its green color and miss out on the full nutritional potential associated with carotenoid accumulation. To ensure red coloration, it's essential to allow the pepper to ripen on the vine under optimal growing conditions.

Bell Peppers vs Tomatoes: Key Differences in Ripening Physiology

Climacteric vs. Non-Climacteric Ripening

A key difference between tomatoes and bell peppers lies in their ripening physiology:

- Tomatoes are climacteric fruits, meaning they continue to ripen after harvest. This is characterized by a burst in respiratory activity and ethylene production.

- Bell peppers, by contrast, are non-climacteric. They do not ripen significantly post-harvest and exhibit different metabolic behavior during the ripening phase.

Professor Baginsky explains:

“The green peppers frequently available in supermarkets are unripe. They still carry chlorophyll-rich chloroplasts and, when fresh, also contain a large amount of the photosynthetic storage substance starch.”

This non-climacteric nature means that the proteins involved in pepper ripening—and by extension, chromoplast differentiation—are fundamentally different from those in tomatoes.

Protein-Level Differences in Bell Pepper and Tomato Ripening

Lower Levels of PTOX and Alternative ATP Production Pathways

One major finding from the RUB study is the limited presence of plastid terminal oxidase (PTOX) in bell peppers. In tomatoes, PTOX plays a role in oxidizing carotenoid intermediates and producing water. However, the study found only trace amounts of PTOX in bell peppers, suggesting a different mechanism at play.

Instead, the researchers observed higher levels of:

- Plastocyanin

- Cytochrome b6/f complex

These proteins are involved in photosynthetic electron transport and suggest that bell peppers repurpose components of their photosynthetic machinery to generate ATP for chromoplast activity during ripening. Unlike tomatoes, which rely more heavily on PTOX-mediated oxygen-dependent pathways for carotenoid synthesis, bell peppers appear to favor a modified electron transport chain that enhances ATP output with lower oxygen use. This may support prolonged chromoplast function during ripening without triggering the climacteric respiratory burst seen in tomatoes.

Additionally, the presence of elevated plastocyanin levels may facilitate a more stable redox environment within the plastids, allowing sustained carotenoid biosynthesis over time. These molecular adaptations highlight the evolutionary divergence in energy metabolism between climacteric and non-climacteric fruits and offer potential targets for bioengineering fruit with extended shelf life or enhanced nutrient profiles.

Sustainable Carotenoid Production in Bell Peppers: Research Applications

Using Chromoplast Engineering to Improve Nutrient Yield

This new understanding of chromoplast development may have broader implications beyond peppers. One promising application is the bioengineering of carotenoid biosynthesis in other plant tissues.

Researchers plan to explore a technique pioneered by a Spanish team, where chromoplast differentiation is induced in leaves via a single enzyme. If successful, this could pave the way for:

- Enhanced carotenoid yields in crops and edible leaves

- Biofortification strategies for malnourishment-prone regions

- Improved shelf-stability and nutrient preservation in food products

Such developments could lead to more sustainable and scalable carotenoid production in agricultural biotechnology.

Proteomic Tools for Analyzing Bell Pepper Ripening

Proteomic Mapping Techniques

To analyze the protein-level changes in bell pepper plastids, researchers used advanced proteomics techniques, including:

- Mass spectrometry (MS) for high-resolution protein identification

- Quantitative proteomic profiling to monitor expression changes over time

- Pride database integration for public data sharing and cross-lab comparison

These tools enabled a comprehensive, time-resolved map of protein transformation from chloroplasts to chromoplasts—paving the way for more granular understanding of plant ripening physiology.

Final Insights: Molecular Biology Behind Bell Pepper Ripening

The RUB study marks a pivotal step in plant biochemistry by decoding how bell peppers undergo visual and metabolic ripening at the molecular level. Unlike climacteric fruits such as tomatoes, bell peppers exhibit a unique ripening strategy that utilizes repurposed photosynthetic proteins, minimal oxygen dependence, and an efficient ATP production pathway.

For lab professionals and plant scientists, these findings offer a new lens through which to view fruit maturation, nutrient accumulation, and metabolic engineering. As we continue to unlock the secrets of plant cell organelles, opportunities for agricultural innovation and nutrition science grow ever brighter—just like a perfectly ripe red bell pepper.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why are green bell peppers less sweet than red ones?

Green bell peppers are unripe and contain more chlorophyll and starch, which masks the sweetness developed later during carotenoid accumulation as they ripen.

When will green bell peppers turn red?

Green bell peppers will only turn red if they remain on the plant long enough for ripening to complete naturally. Because peppers are non-climacteric fruits, they do not ripen well after harvest. If picked while still green, the transition from chloroplasts to carotenoid-rich chromoplasts may stall, and the fruit may never turn red.

How do bell peppers and tomatoes differ in ripening?

Tomatoes are climacteric and ripen post-harvest with a respiratory surge, while bell peppers are non-climacteric and undergo all ripening on the plant, with different metabolic pathways.