Rheology testing inherently involves subjecting materials to mechanical stress. This mechanical stress significantly escalates the risk profile when handling hazardous fluids. Laboratory professionals must recognize a critical danger. The very act of measuring viscosity and viscoelastic properties can transform a contained sample into a source of toxic exposure. This occurs through shear-induced aerosolization or volatile release. Standard safety data sheets (SDS) often address static handling. However, they rarely account for the dynamic conditions present within a rotational rheometer or capillary system. Operators need to look beyond basic personal protective equipment (PPE). They must consider the complex interaction between fluid dynamics and chemical containment. Establishing a robust safety framework for these measurements protects personnel, preserves instrument integrity, and ensures data accuracy.

Assessing aerosolization risks when testing hazardous fluids

High-speed rotation and oscillation during rheological measurements generate centrifugal forces. These forces can eject hazardous fluids from the measurement gap. This ejection creates a primary exposure vector for laboratory personnel. It is particularly dangerous when testing low-viscosity toxic solvents or biofluids. Even highly viscous materials can fracture at high shear rates, releasing particulate matter or droplets into the surrounding environment.

The risk of aerosolization increases non-linearly with shear rate. As the measuring geometry spins, the fluid at the edge of the geometry experiences the highest velocity. This makes it the most likely point of failure for containment. Laboratory managers must assume that any open-system rheometer test has the potential to generate airborne contaminants.

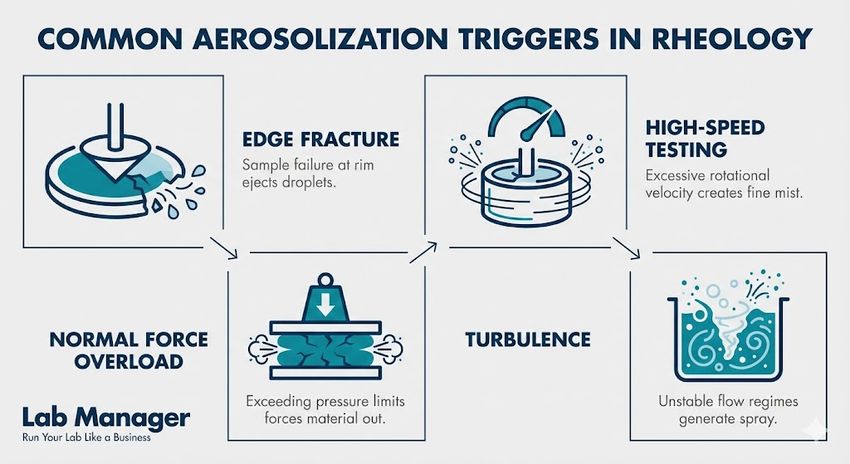

This infographic illustrates the four common triggers of aerosolization during rheological testing: Edge Fracture, High-Speed Testing, Normal Force Overload, and Turbulence.

GEMINI (2026)

Common aerosolization triggers in rheology:

- Edge fracture: Polymer melts or concentrated solutions may break at the meniscus, flinging material outward.

- High-speed testing: Mimicking spraying or coating processes often requires rotational speeds that overcome surface tension.

- Normal force overload: Excessive gap compression during loading can squeeze fluid out before the test begins.

- Turbulence: Low-viscosity fluids in wide gaps can become turbulent, splashing out of concentric cylinder cups.

A critical oversight in many laboratories is the reliance on standard room ventilation. The OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200) and the hierarchy of controls prioritize engineering controls that isolate the hazard at the source over reliance on PPE. For a rheometer, the "source" is an unsealed gap often located inches from the operator's breathing zone during sample trimming.

Operators often underestimate the volume of aerosol generated by "micro-liter" samples. However, the surface-area-to-volume ratio in a rheometer gap is extremely high, promoting rapid volatilization of hazardous components even from minimal sample sizes.

Engineering controls for containing hazardous fluids in rheometers

Engineering controls provide the most effective barrier against exposure during the rheological characterization of hazardous fluids. These controls range from simple draft shields to fully integrated glovebox solutions, depending on the biosafety level (BSL) or toxicity of the sample. The primary challenge lies in isolating the hazard without compromising the sensitive air bearing of the rheometer, which is susceptible to turbulence and pressure fluctuations.

Placing a rheometer inside a standard chemical fume hood often degrades data quality. The high airflow velocity required for fume hood certification can induce vibration in the instrument. It also creates air currents that affect temperature control systems. Furthermore, the corrosive nature of many hazardous fumes can damage the precision air bearing if the intake air is not properly filtered or sourced from a clean supply.

Effective containment strategies:

- Custom enclosures: Plexiglass enclosures fitted with HEPA or carbon filtration allow for viewing while maintaining negative pressure.

- Snorkel extractions: Positioned directly near the geometry, these provide localized capture for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) without creating high-velocity drafts across the entire instrument.

- Glovebox integration: For highly toxic or oxygen-sensitive materials, the entire rheometer is housed in an inert atmosphere glovebox, requiring feedthroughs for power and data.

- Solvent traps: These passive accessories cover the sample area to minimize evaporation and fume release during the test itself.

When utilizing a solvent trap, the operator creates a micro-environment that serves a dual purpose. It prevents the drying of the sample, which would ruin the rheological data. It also creates a physical barrier that contains vapors. However, solvent traps are not pressure vessels. They delay release but do not eliminate the need for external ventilation if the seal is breached or during sample loading.

Facilities frequently neglect the air bearing supply and electronics cooling when enclosing rheometers. If the instrument's cooling fans pull intake air from within a contaminated enclosure, internal electronics can corrode. Additionally, ensuring the compressed air supply for the bearing is drawn from outside the hazard zone is mandatory for long-term instrument survival.

Managing thermal and pressure hazards in rheology testing

Elevated temperatures and pressures exponentially increase the danger profile of hazardous fluids during rheological characterization. Heating a sample near its flash point or boiling point within a rheometer can lead to rapid expansion, seal failure, or auto-ignition. Standard Peltier plates or fluid baths are typically open systems. This means any increase in temperature directly increases the vapor pressure of toxic volatiles released into the lab.

Closed pressure cells are the required geometry choice for testing hazardous fluids above their boiling points or under simulated process conditions. These cells utilize magnetic couplings to transfer torque from the rheometer motor to the bob inside the cup. This effectively seals the sample from the operator. This isolation protects the user from toxic fumes and high-pressure jets in the event of a seal failure.

Critical considerations for pressure cell usage:

- Seal compatibility: The O-rings utilized (Viton, Kalrez, PTFE) must be chemically resistant to the specific hazardous fluid to prevent degradation under heat and stress.

- Pressure limits: Operators must strictly adhere to the manufacturer’s maximum pressure rating, which often decreases as temperature increases.

- Headspace volume: Overfilling a pressure cell leaves no room for thermal expansion, leading to hydraulic lock and potential catastrophic rupture.

- Cool-down protocols: Opening a cell before it has returned to safe temperatures can result in flash boiling and immediate exposure.

Temperature calibration presents a unique safety challenge with hazardous fluids. Traditional methods involving external thermometers may expose the operator to the open sample. Laboratories should rely on internal temperature sensors that have been validated against non-hazardous standards, avoiding the need to probe the toxic sample directly.

A common mistake in high-pressure rheology is assuming the magnetic coupling is decoupling solely due to sample viscosity. This mechanical slip can indicate bearing friction caused by particulate contamination rather than fluid properties. Since this is often an early sign of potential seal or bearing failure, ignoring it can lead to excessive heat buildup within the coupling assembly; operators should consult the instrument manufacturer regarding specific torque limits and troubleshooting.

Protocols for safely loading and trimming hazardous samples

The moments of sample loading and trimming represent the highest risk periods for operator exposure to hazardous fluids. During the actual test, the sample is often partially enclosed or moving too fast to approach. However, loading requires the operator to work within inches of the material. Manual manipulation of spatulas, pipettes, and trimming tools brings gloved hands into direct contact with toxic or biohazardous substances.

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) must dictate specific loading techniques that minimize contact time and potential for spills. For example, using a reverse-pipetting technique for low-viscosity hazardous fluids prevents dripping and ensures accurate volume placement on the lower plate. Overloading the geometry requires trimming the excess material, which generates waste that must be immediately managed.

Best practices for hazardous sample loading:

- Pre-weighed aliquots: preparing samples in a separate containment zone reduces the time the container is open at the rheometer.

- Disposable geometries: Using single-use plates and cylinders eliminates the high-risk step of cleaning toxic residues from permanent fixtures.

- Wiping protocols: Trimming excess sample should be done with a single, continuous motion using a dedicated wiper to prevent smearing material onto the shaft.

- Protective barriers: A breakdown of the sample structure during loading can cause splashes; face shields should be mandatory even if a sash is present.

Ergonomics plays a subtle but vital role in safety. Loading a rheometer inside a glovebox or deep fume hood can force the operator into awkward postures, reducing dexterity. Reduced dexterity increases the likelihood of spills or dropped tools. Labs should invest in height-adjustable benches or extended-length tools to maintain precise control during the loading phase.

Decontaminating rheometer geometries after hazardous testing

Proper decontamination ensures the removal of hazardous residues from delicate sensor surfaces without compromising measurement accuracy or operator safety. The cleaning process typically involves solvents that may themselves be hazardous. This creates a secondary exposure risk that must be managed. Operators should never spray cleaning agents directly onto the rheometer head, as this can drive contaminants into the air bearing or electronics.

Instead, cleaning should be performed using solvent-saturated wipes or by immersing removable geometries in a dedicated ultrasonic bath located inside a fume hood. For permanent lower plates, a "sacrificial" cleaning run can be employed where a cleaning gel or polymer is loaded, cured, and peeled off, removing surface contaminants with it. This method minimizes physical scrubbing and solvent use at the machine.

Ensuring safe workflows for hazardous fluid rheology

Safety protocols for handling hazardous fluids in rheology testing requires a multi-layered approach involving risk assessment, engineering controls, and rigorous operational procedures. Laboratories must address the specific dangers of shear-induced aerosolization and thermal expansion to protect personnel from toxic and biological exposure. Integrating containment solutions like solvent traps and pressure cells ensures that data quality remains high without compromising the safety of the workspace. By treating every microliter of sample as a potential hazard, rheologists can maintain a secure analytical environment.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.