Selecting the optimal instrumentation for trace metal analysis remains a pivotal decision for analytical laboratories aiming to balance sensitivity, throughput, and cost-efficiency. Historically, laboratories relied on Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) for single-element analysis, but the demand for higher throughput and multi-element capabilities drove the industry toward plasma-based techniques. Today, ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy) and ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) represent the gold standards for elemental detection.

While both techniques utilize high-temperature argon plasma to atomize and ionize samples, the method of detection—optical emission versus mass-to-charge ratio—fundamentally alters their applicability. This distinction is not merely academic; it dictates suitability for specific matrices, determines maintenance schedules, and defines compliance strategies for regulated sectors such as pharmaceuticals, environmental testing, and metallurgy. Understanding these nuances is essential for laboratory managers and spectroscopists ensuring compliance with rigorous standards like ICH Q3D, USP <232>/<233>, and various EPA regulations.

Operating Principles: How ICP-OES and ICP-MS Work

To determine which instrument suits a specific analytical workflow, one must first distinguish the underlying physics of detection. Both systems share a sample introduction system—typically consisting of a peristaltic pump, nebulizer, and spray chamber—that generates a fine aerosol. This aerosol is injected into the base of a plasma torch. The argon plasma, generated by radiofrequency (RF) energy interacting with a magnetic field, reaches temperatures ranging from 6,000 to 10,000 K. This extreme thermal environment efficiently desolvates, vaporizes, atomizes, and ionizes the liquid sample.

ICP-OES: Atomic Emission and Optical Design

In ICP-OES, the measurement relies on photons emitted by excited atoms and ions as they relax from a high-energy state to a lower stable state. Each element emits a characteristic set of specific wavelengths, creating a unique spectral fingerprint. The instrument’s optical system, often a polychromator utilizing an Echelle grating and prism, separates these wavelengths into a two-dimensional pattern.

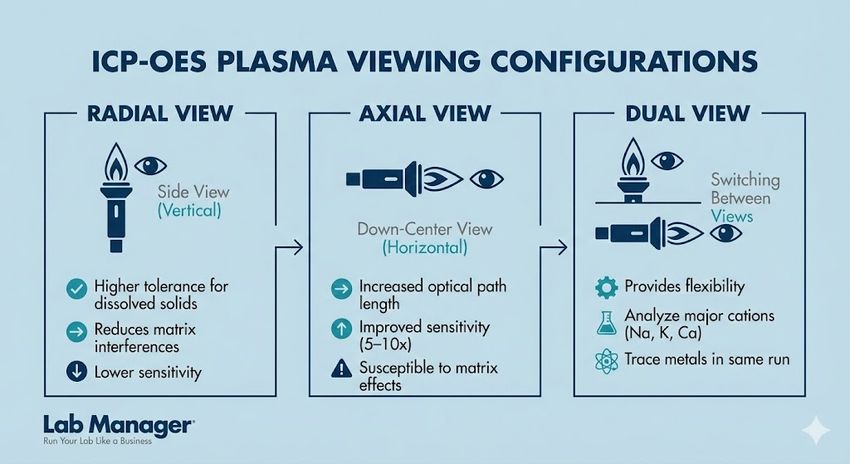

Modern systems employ solid-state detectors, such as Charge-Coupled Devices (CCD) or Charge-Injection Devices (CID), which are often cooled to reduce thermal noise. These detectors allow for the simultaneous measurement of the analyte peak and the background emission, significantly improving precision. The signal intensity recorded is directly proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample. A critical design feature in modern ICP-OES is the plasma viewing configuration:

Choosing the correct plasma viewing configuration is essential for optimizing ICP-OES performance.

GEMINI (2026)

- Radial View: The plasma is viewed from the side (vertical orientation). This offers higher tolerance for dissolved solids and reduces matrix interferences but offers lower sensitivity.

- Axial View: The plasma is viewed down the center (horizontal orientation). This increases the optical path length, improving sensitivity by 5–10 times, but is more susceptible to matrix effects.

- Dual View: Most modern instruments allow switching between views, providing flexibility for analyzing both major cations (Na, K, Ca) and trace metals in the same run.

ICP-MS: Ion Extraction and Mass Separation

ICP-MS differs significantly after the plasma stage. Rather than measuring light, the instrument physically extracts ions from the atmospheric pressure plasma into a high-vacuum region. This transition occurs through an interface consisting of a sampling cone and a skimmer cone, usually made of nickel or platinum.

Once inside the vacuum, ions are focused by a series of electrostatic lenses (ion optics) which guide the ion beam while rejecting neutral species and photons. The ions are then separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) using a mass analyzer. The most common analyzer is the Quadrupole, which acts as a mass filter, allowing only one specific m/z to pass through at a time. For higher resolution needs, Magnetic Sector fields or Time-of-Flight (TOF) analyzers are used. An electron multiplier detector then counts the individual ions. This direct counting of atoms allows ICP-MS to achieve detection limits orders of magnitude lower than optical methods, but it also necessitates a much more controlled vacuum environment involving turbomolecular pumps.

Sensitivity and Detection Limits: Comparing ICP-OES vs. ICP-MS

The primary differentiator between the two techniques is sensitivity. Trace metal analysis requirements have become increasingly stringent, driving the adoption of instrumentation capable of detecting analytes at ultra-trace levels.

ICP-MS is the superior choice for ultra-trace detection, typically offering detection limits in the parts-per-trillion (ppt) range. This capability is critical for applications requiring the quantification of toxic heavy metals—such as Lead (Pb), Arsenic (As), Mercury (Hg), and Cadmium (Cd)—at extremely low concentrations. For example, in the semiconductor industry, where purity is measured in "nines" (e.g., 99.9999%), or for drinking water analysis where regulatory limits are strict, ICP-MS is often the mandatory technique.

Conversely, ICP-OES generally operates in the parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-million (ppm) range. While less sensitive than mass spectrometry, it excels in robustness and the ability to handle high Total Dissolved Solids (TDS). ICP-OES can typically tolerate TDS levels up to 30% with specialized sample introduction kits, whereas ICP-MS is generally limited to <0.2% TDS to prevent cone blockage and signal drift. This makes ICP-OES the preferred tool for brine analysis, plating baths, and geological digests where extensive dilution required for MS would introduce error or dilute trace analytes below detection.

Summary of Performance Metrics

Feature | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|

Detection Limits | 1–10 ppb (typically) | 1–10 ppt (typically) |

Working Range | Linear up to 10^6 (High dynamic range) | Linear up to 10^9 (Requires pulse/analog modes) |

Isotopic Analysis | Not possible | Excellent capability |

TDS Tolerance | High (up to 30% with argon humidifier) | Low (< 0.2% without gas dilution/HMI) |

Speed | Very Fast (Simultaneous optics) | Fast (Scanning speed dependent) |

Precision | Excellent (0.2–0.5% RSD) | Good (1–3% RSD) |

Managing Interferences for High Accuracy in Trace Metal Analysis

Ensuring accuracy in trace metal analysis requires a robust strategy for managing interferences. The nature of these interferences differs dramatically between the two techniques, requiring different mitigation strategies in the laboratory method.

Spectral and Physical Interferences in OES

ICP-OES suffers primarily from spectral overlaps, where the emission lines of two elements are too close to be resolved by the optical system. For instance, analyzing traces of Zinc in a Copper matrix can be challenging due to the rich emission spectrum of Copper which blankets the UV region. Laboratories mitigate this using high-resolution optics (Echelle gratings) and by selecting alternative interference-free wavelengths. When overlaps are unavoidable, Inter-Element Correction (IEC) factors are mathematically applied to subtract the interfering signal.

Physical interferences, caused by differences in viscosity or surface tension between samples and standards, are also common in OES. These are typically managed by using a peristaltic pump for consistent flow and employing Internal Standards (such as Yttrium or Scandium) that mimic the behavior of the analytes to correct for transport efficiency variations.

Isobaric and Polyatomic Interferences in MS

ICP-MS faces isobaric interferences (isotopes of different elements with the same mass, e.g., Cd-114 and Sn-114) and polyatomic interferences. Polyatomic ions are molecular species formed in the plasma or interface from the combination of argon, solvent, and matrix elements. A classic example is the formation of Argon Chloride (Ar-40 Cl-35 +) at mass 75, which directly interferes with the only isotope of Arsenic (As-75). In a chloride-rich matrix like hydrochloric acid or seawater, this can cause massive false-positive results for Arsenic.

Modern ICP-MS instrumentation addresses these challenges using Collision/Reaction Cells (CRC) or Universal Cell Technology (UCT). These cells are located before the mass analyzer and are pressurized with a gas:

- Collision Mode (Kinetic Energy Discrimination - KED): An inert gas like Helium is introduced. Polyatomic ions, being larger than analyte ions, collide more frequently with the Helium atoms, lose more kinetic energy, and are filtered out by a potential barrier. This is the standard mode for multi-element environmental analysis.

- Reaction Mode: A reactive gas (like Ammonia, Oxygen, or Hydrogen) is used to chemically react with the interference (shifting its mass) or the analyte (mass-shifting the target to an interference-free zone). This provides the lowest detection limits for difficult elements.

Applications: Drinking Water, Soil, Alloys, and Pharma (ICH Q3D)

The choice of instrument often depends heavily on the specific industry application, the sample matrix involved, and the regulatory framework governing the results.

Environmental Testing: Soil, Water, and Waste

In environmental laboratories, the matrix dictates the method. For drinking water analysis, the objective is verifying safety against low-level contaminants. ICP-MS is the industry standard here (e.g., EPA Method 200.8) because it can simultaneously measure a full suite of elements—from trace toxic metals (Lead, Arsenic, Uranium) to macro nutrients—in a single run with minimal sample preparation.

However, for soil, sludge, and wastewater analysis, where samples often contain high levels of dissolved solids and the target elements are present at higher concentrations, ICP-OES is often preferred (e.g., EPA Method 200.7). ICP-OES handles the heavy matrix of digested soil samples with less maintenance downtime compared to the cone cleaning required for MS systems running similar samples. Furthermore, OES is ideal for detecting sulfur and phosphorus, which are difficult for standard MS due to interferences.

Pharmaceuticals: USP <232>/<233> and ICH Q3D

The implementation of ICH Q3D guidelines and USP General Chapters <232> (Limits) and <233> (Procedures) has revolutionized pharmaceutical analysis, mandating the monitoring of elemental impurities in drug products. The choice of technique depends entirely on the Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) limits and the daily dosage.

For oral drug products with higher PDE limits, ICP-OES sensitivity is often sufficient to quantify the "Big Four" (Cd, Pb, As, Hg) and other Class 2A/2B elements at the required "J-value" (target concentration). However, for parenteral (injected) or inhalation routes where PDE limits are significantly lower, or for drug products with high daily doses (>10g/day), the required detection limits often fall below the capability of ICP-OES. In these scenarios, ICP-MS becomes the necessary technique. Additionally, ICP-MS is required when "speciation" is needed—for example, distinguishing inorganic Arsenic from organic Arsenic species, which have different toxicity profiles.

Food Safety, Forensics, and Petrochemicals

In food safety, trace metal analysis ensures consumer protection from bioaccumulated metals. ICP-MS is critical here for detecting low levels of mercury in fish or arsenic in rice. Coupled with Liquid Chromatography (LC-ICP-MS), it allows for speciation analysis, distinguishing between toxic inorganic arsenic and less toxic organic forms.

In forensics, the ability of ICP-MS to measure isotopic ratios provides a unique fingerprinting capability. This is utilized in identifying the source of lead in bullets or comparing glass fragments found at a crime scene.

Conversely, the petrochemical industry relies heavily on ICP-OES for the analysis of wear metals and additives in lubricating oils (ASTM D5185). The organic matrix is often diluted in kerosene or xylene. ICP-OES is preferred here because it can robustly analyze Iron, Copper, and Zinc wear particles without the clogging issues associated with MS cones, and the detection limits required (ppm level) are well within the OES range.

Operational Efficiency: Cost, Automation, and Laboratory Compliance

Beyond analytical capability, laboratory management must consider the operational footprint of the instrumentation. This includes capital expenditure, running costs, data integrity, and automation potential.

ICP-OES is generally more cost-effective to acquire, often costing 30–50% less than a standard ICP-MS unit. However, the operational expenditure (OpEx) calculus is complex. While both systems consume significant amounts of Argon gas (15–20 L/min), ICP-MS generally requires ultra-high purity grades (99.999% or higher) to maintain low background noise. The most significant OpEx difference lies in consumables; ICP-MS sampling and skimmer cones are expensive and require regular replacement or cleaning (conditioning). Furthermore, ICP-MS often necessitates a cleaner laboratory infrastructure (Class 1000 cleanroom hoods) to prevent environmental contamination at the ppt level, adding to facility costs.

ICP-MS requires a higher degree of operator expertise to manage vacuum systems and interference correction equations. However, the throughput of ICP-MS has increased with the integration of rapid sample introduction systems (vacuum, valve-based) which can reduce sample uptake and washout times to under 60 seconds per sample.

Both systems benefit from modern automation and software designed for regulated environments (21 CFR Part 11). Autosamplers with integrated rinsing protocols, auto-dilution systems (to handle over-range samples or reduce matrix suppression), and intelligent software that monitors QC failures and automatically re-runs samples are standard. This automation allows laboratories to run unattended overnight batches, significantly improving turnaround times and reducing the cost per analysis.

Conclusion: ICP-OES vs. ICP-MS—Choosing the Best Technique

The decision between ICP-OES and ICP-MS for trace metal analysis is rarely a binary choice of "better" or "worse," but rather a calculation of fitness for purpose. ICP-MS offers unrivaled sensitivity and isotopic capability, making it indispensable for drinking water, clinical, and parenteral pharmaceutical testing where detection limits are paramount. It is the only viable path for ultra-trace quantification and speciation.

Conversely, ICP-OES provides a robust, cost-effective workhorse solution for soil, wastewater, petrochemicals, and alloys, where high matrix tolerance, speed, and long-term stability are prioritized over ultra-trace detection. It remains the technique of choice for samples with high total dissolved solids.

Laboratory professionals must evaluate their specific Data Quality Objectives (DQOs), regulatory requirements, and budget constraints. In many high-throughput commercial laboratories, a dual-platform approach—utilizing ICP-OES for screening and high-level analysis and ICP-MS for low-level regulatory compliance—provides the most efficient and comprehensive analytical strategy.

This article was created with the assistance of Generative AI and has undergone editorial review before publishing.